يوم الأحد، ١١ ربيع الثاني ١٤٢٨

| 20 | ٢ | |||

| 21 | ٣ | |||

| 22 | ٤ | |||

| 23 | ٥ | |||

| 24 | ٦ | |||

| 25 | ٧ | |||

| 26 | ٨ | |||

| 27 | ٩ | |||

| 28 | ١٠ | |||

| 29 | ● | ١١ | ||

| 30 | ١٢ | |||

| 1 | ١٣ | |||

| 2 | ١٤ | |||

| 3 | ١٥ | |||

| 4 | ١٦ | |||

| 5 | ١٧ | |||

| 6 | ١٨ | |||

| A Rose-Red City Half as Old as Time |

Everything else – the Greek islands, Knossos, Phaestos, the Acropolis, Jerusalem, Wadi Rum, the Nile, Karnak, Luxor, the Pyramids, the Sphinx, Cairo – was filler. Glorious, life-altering filler, indisputably – but filler nonetheless. Like the Cyclades around Delos, this journey was centered around one singular, unabating, specific goal: I. would set foot. in Petra!

John William Burgon described it beautifully in a poem for which he earned the Newdigate Prize in 1845. Almost as tragic as the ruined glory of Petra, though, is the story of this sonnet – Burgon's description came entirely from second-hand accounts: He had never seen the rose-red city with his own eyes.

|

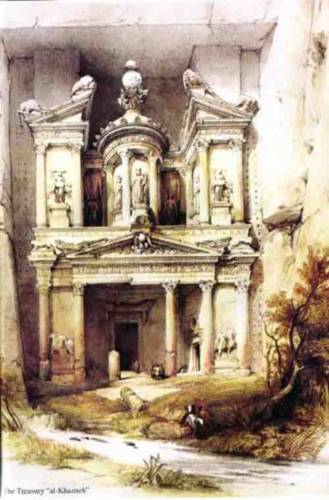

That's my favorite picture of

Did the carvers leave this one untamable wall when Petra was still vibrant, alive, and busy with labor? or at the end when time had simply run out? Was it abrupt when they put away their tools? or did one or two old workers keep at it, less and less often, until they became too old, too tired, too confused to continue? Did they blame themselves? their gods? the weather? the rock? the jinn? Was it a bitter reminder to them of failure? Or did they, like me, think it was one of the most beautiful things on earth?

So how important was Petra to me? Well, I wrote the rough draft of the trip report in as it happened; but when it came time to prepare the final result, I started with this page, then I went back to page 1. Even the color-scheme of this trip report nods to Petra. I cannot immediately think of the goal in my life that will supersede the drive to visit the rose-red city.

So this is how that day went ...

| Leaving the Taybet Zaman |

The Taybet Zaman was a hotel that we definitely could have gotten used to. But even if we could have afforded the 92 JD ($130) a night, we couldn't have afforded the time. So we checked out early and hit the road for Petra. We did, however, stop in at the breakfast buffet, where we enjoyed eavesdropping on a nearby table: A French mother was trying to teach her very young child English by making him order the beverages and thank the waiter.

And jeez, before I move on, I just have to dwell on the social complexity of that situation:

- In an Arabic-speaking country, a French-speaking family felt the need to use English as (it's disturbing even to type it) the "linga franca."

- This mother thought English was so important that she was teaching it to her toddler.

- The French have an undeserved reputation for linguistic belligerence, but I have seen no evidence of this either in France or outside it. On this trip especially we encountered group after group of French tourists (there was a major travel promotion there in the spring of this year), and all would eagerly speak with me and Billy in English, even after I spoke to them in French and made it clear that I would be happy to continue doing so. (If nothing else, traveling teaches that everything everyone says is wrong.)

So it made me a little sad to hear the kid and the waiter struggling along in English. I don't feel comfortable having an unfair advantage, but Billy and I really won the language lottery when we were born.

| Petra |

Not realizing that we had passed the historic site as we looked for the Taybet Zaman the prior evening, our day's journey began in the wrong direction. Fortunately, this was a detour of only about 10 km – and we found the signage clear and plentiful once we were facing toward it. I dropped Billy at the visitors center and then went to park the car, which required paying 3.000 JD ($4.24) (no surprise there) and signing, for no discernable reason, a piece of paper with nothing written on it except all of the other drivers' signatures, all oriented randomly on the page.

The attendant was surprised that I asked whether I should sign in Arabic or English (none of the other signatures were in Latin script), and was astonished when I signed it correctly in Arabic. People didn't seem particularly amazed that I could speak a bit of Arabic, even though very few tourists can, and even though the language is quite challenging – but, strangely, they were often flabbergasted to find that I could read and write it, which really isn't all that difficult.

| World Heritage Site | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

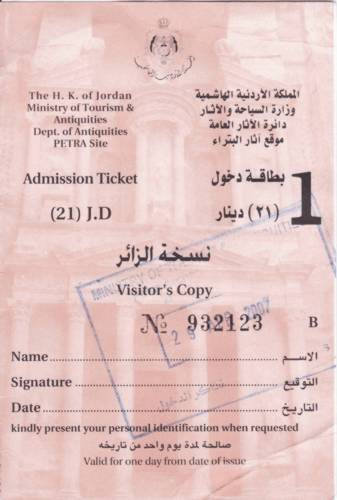

Anyway, I reconnoitered with Billy and we bought our tickets and made our way in.

|

| Entrance Ticket to Petra (They love the rubber stamp in the Middle East.) |

For a place so burdened with expectations, Petra delivered admirably. The pictures, however, are likely the worst of the trip: Because of Billy's fatigue, we rode through the Siq in a horse-drawn cart; through the valley on camels; and up to the Monastery on the backs of donkeys. My pictures, therefore, reflect a shaky platform, an uncertainty as to balance, and often an unpredictable speed. Even the good pictures, however, cannot begin to reflect the experience. Because of the narrow valley, it is impossible in some places to stand far enough back to frame an entire grand façade. In other places, a choice must be made: The picture can reflect (1) the scope or (2) the detail, but rarely both. The following pictures illustrate what I'm talking about:

|

Here's a nice entrance to one of the tombs, with a little detail that's worth noticing. |

But I've jumped ahead just to make a point about the photographic challenges of Petra. Let's get back to the proper sequence of events: Billy and I are bouncing downhill on a rutted dirt road (and occasional Roman-era cobblestones), squeezed into the passenger area of a horse cart with the driver, racing past some monuments and tombs that would be absolutely astonishing if the Nabatean city of Petra didn't await just a few hundred meters through the narrow Siq.

|

I was a bit concerned about the fact that we would be using animals in Petra, as a lot of tourist sites (especially in this part of the world) have a reputation for mistreatment of animals. So I was delighted to see this sign just past the ticket booth. |

It bears note that this didn't open the floodgates to Petra. The site remained largely closed to outsiders until after World War I.

|

As the horse cart rumbled along scattering other tourists in its wake, finally we came to the Siq itself. |

So we hopped out of the cart, paid the driver, arranged for the pick up later, and set about seeing Petra – beginning with

Fans of the unfortunately named movie Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade will recognize the Treasury as the final site in which the holy grail was placed. In truth, it was probably a temple (or maybe a tomb) – but it is called "The Treasury" because the Bedouin believed that the urn above the doorway held treasure, and spent decades trying fruitlessly to break it open and release a shower of gold. Bullet marks and other scars from these efforts remain visible to this day. Fortunately, such desecration has come to a stop: Petra is a protected site, and modern science lets us know that these legends never held a grain of truth: The urn, like the rest of the façade, is solid rock; the only treasure is the architecture that a few greedy souls tried to destroy.

|

It was spectacular finally just to stand in front of the Treasury. Here's what it looked like: |

At first we tried to walk a bit to see some of the edifices up close. This was nice for as long as it lasted, as we got our first taste of the depth of Petra along the Street of Façades.

|

|

You'd think that with the narrow canyons and sheer walls and sheltered tombs that there would be some respite from the blazing sun in Petra – but there is not. It beats straight down, mercilessly and unceasingly. And the tombs have a heavy, stuffy air that offsets the shade they provide. So we stopped in one of the snack bars (which are placed every 100 m in Petra) for Cokes and Snickers bars (the latter being smaller and less sweet than what we have in the U.S.), and created trilateral friction among ourselves and the natives: Camel rides through the Wadi Musa are easy to come by, and we intended to ride part of the way; but we were uncertain how long we wanted to walk before hiring camels. A group of men tried to interest us in their camels, but we demurred because of this uncertainty. Unfortunately, we demurred by saying, "maybe later; we haven't decided" instead of "absolutely not." In the snack bar, a young man took our requests and handled our money and change. We assumed that he worked there, but it turned out that he was just building a relationship (as is the custom) in the hope of further capitalistic interaction. By this point, we had been sitting for a few minutes and Billy had let me know that he was exhausted in the sun and didn't want to walk any further down the valley, so the young man, overhearing us, asked us to speak to his friend, Ahmed Abdullah, about camels. We struck a deal with Ahmed Abdullah – and when the first group of camel owners saw that we had done so, they became quite fussy with us, saying that we had an obligation to attempt a deal with them before going to someone else. We protested confusion and ignorance, and apologized for the misunderstanding; this placated their anger toward us, but they remained quite vocally annoyed at Ahmed Abdullah for stealing our business, shouting to him in Arabic that I didn't understand, and then shouting to us that he is unethical.

You'd think that with the narrow canyons and sheer walls and sheltered tombs that there would be some respite from the blazing sun in Petra – but there is not. It beats straight down, mercilessly and unceasingly. And the tombs have a heavy, stuffy air that offsets the shade they provide. So we stopped in one of the snack bars (which are placed every 100 m in Petra) for Cokes and Snickers bars (the latter being smaller and less sweet than what we have in the U.S.), and created trilateral friction among ourselves and the natives: Camel rides through the Wadi Musa are easy to come by, and we intended to ride part of the way; but we were uncertain how long we wanted to walk before hiring camels. A group of men tried to interest us in their camels, but we demurred because of this uncertainty. Unfortunately, we demurred by saying, "maybe later; we haven't decided" instead of "absolutely not." In the snack bar, a young man took our requests and handled our money and change. We assumed that he worked there, but it turned out that he was just building a relationship (as is the custom) in the hope of further capitalistic interaction. By this point, we had been sitting for a few minutes and Billy had let me know that he was exhausted in the sun and didn't want to walk any further down the valley, so the young man, overhearing us, asked us to speak to his friend, Ahmed Abdullah, about camels. We struck a deal with Ahmed Abdullah – and when the first group of camel owners saw that we had done so, they became quite fussy with us, saying that we had an obligation to attempt a deal with them before going to someone else. We protested confusion and ignorance, and apologized for the misunderstanding; this placated their anger toward us, but they remained quite vocally annoyed at Ahmed Abdullah for stealing our business, shouting to him in Arabic that I didn't understand, and then shouting to us that he is unethical.

Now as I write, I know that most of the people reading this will think, "That's crazy. You can make your camel arrangements with anyone. It's the customer's choice. Period." What I can tell you now, with better understanding and a little hindsight, is that (in the culture of rural Jordan) the angry fellow was completely in the right: We had established a obligation to do business with him if we did business in his vicinity. And Ahmed Abdullah's behavior was, indeed, unethical. It took me a few more days and a few more interactions (mostly successful ones) before I really understood the system and my obligations within it. But it was clear to me that we were on the wrong side from the start: Ahmed Abdullah's behavior and body language reflected guilt and the wish for a quick getaway.

So we did make a quick getaway, down the Wadi Musa, past the Amphitheatre and a few temples, down the Colonnaded Street, and to the

|

|

On the Colonnaded Street in "downtown ancient Petra" we disembarked from our camels and were sold on a donkey ride up to

So up we went. And it was really cool. And I hope that if we overpaid, at least our overpayment might help to equalize the economic imbalance that causes one of the most amazing places on earth to be also one of the poorest.

Anyway, our guide was fun. He told us about the economic and educational privation of his Bedouin people; apparently they long for a decent school system, as there is a substantial difference in quality between the schools in Amman (the capital) and this area far to the south. He told us that he never studied English (which he spoke pretty well), but, rather, picked it up from the tourists; he said that actually he didn't speak "English," but rather "tourist English." And he shared with us his aspiration of someday having four wives (as is allowed in Jordan). (We asked him if this system didn't leave a lot of men with no wife, and he said yes and fell silent, as if this question had cost him a lot of sleepless nights.) To his credit, he jogged alongside us all the way up the long mountain path, as we were sitting on his only two donkeys. I offered to let him ride for a while, as I was not exhausted but merely needed to make sure that Billy was provided for. But he wouldn't hear of it, insisting that he was accustomed to this work as he huffed and puffed alongside us.

|

The path that the donkeys ported us on was a bit treacherous: |

We rested at the top (more Snickers and Cokes), and then made our way down as we had come, eating in the restaurant in downtown ancient Petra, and then reconnoitering with Ahmed Abdullah for the camel ride back to the Treasury. This involved lots of other camel owners yelling at Ahmed Abdullah (but, fortunately, not at us; it must have been an unrelated transgression). Apparently, he doesn't have a lot of friends in the camel world of Petra.

We rode out, past the Royal Tombs.

|

|

Then we got back on our camels for the ride back to the Treasury. This was where it became self-evident to me that Ahmed Abdullah traveled everywhere he went leaving a wake of frustration, confusion, and acrimony. This is not to say that it wasn't partly my fault; Billy understood the negotiations as Ahmed Abdullah had understood them: that we would owe 20.000 JD ($28.25) each for the trip down to the Colonnaded Street and then back to the Treasury. But I thought we would owe only 7.000 JD each ($9.89), which would have been the cost for the (shorter) one-way trip. In my defense, though, it would have been easier to understand if our negotiation hadn't come in the midst of lots of yelling and a fast getaway.

The money thing was only a problem, though, insofar as I didn't have the 40.000 JD to settle up with Ahmed Abdullah. Fortunately, he had a friend nearby who was able to take my last hundred dollar bill, give me back $40, and give Ahmed Abdullah his share. So I lost $3.47 on the quick-and-dirty 3:2 exchange rate, but I was able to put Ahmed Abdullah behind me.

So we met up with the horse cart boy and exited the Siq as we had come in. When the Nabateans ran the place, there were several routes in and out of Petra, as it made its name and fortune on trade. But now, to protect the site, there's only one way in and one way out. I had hoped to get some pictures in the Siq to highlight the differences between what one finds there and what one finds in the Wadi Musa – but this time the driver was in a hurry, racing past other carts and bellowing for pedestrians to clear the way in as many languages as he could remember.

Considering the money situation, I was worried that I still owed something to the horse cart guy. But fortunately, he didn't even seem to want a tip. As soon as he got us to the entry gate, he started negotiating with other tourists before we could even scramble out of the cart.

So Petra was a financial chokepoint for the trip: 42.000 JD ($59.32) for the two admission tickets, 30.000 JD ($42.37) for the horse cart, $60 for the camels, 60.000 JD ($84.75) for the donkeys, 24.000 JD ($33.90) for two meals in the restaurant on the Colonnaded Street. So, not including tips, Cokes, and Snickers bars, we spent about $280. I came to the perspective that the ruined, but spectacular, irrigation flumes of the Nabateans had magically transformed to work on money instead of water. But Petra was the focus of the entire vacation, and I'm still glad that I didn't skimp. We saw what we wanted to see, without feeling rushed, and Petra was an immensely satisfying experience.

| The Desert Camp |

Considering the fact that I was running out of both Jordanian and American currency, and didn't want to find out what would happen if I came up short, my first order of business outside Petra was to find an ATM and take out 250.000 JD, which I anticipated would last me through our departure. (In fact, 150.000 JD would have been sufficient.)

Then we bought gas and had the first of only two experiences where someone actually tried to trick us out of money. The guy stopped the pump at 5.000 JD, pretending that he thought that's what I wanted. When I told him I wanted a fill-up, he said we would just add 5.000 JD to the total. Then, he attempted to convince me that we needed to add the 5.000 JD twice, which he endeavored to do by (1) placing himself between me and the readout on the gas pump, (2) obfuscating the total, (3) speaking English pretty well when necessary, and (4) not understanding English when it suited his convenience. It was easy to resolve: I stood my ground, walked around him to the pump, and spoke Arabic to him – but it was a disappointment to encounter this behavior. Jordan has a reputation as a very honest, welcoming culture, and I'd hate to see that cultural climate change. I should acknowledge though that he was just a kid, and had a friend staffing the pump with him, and was probably trying to show off. Still, it bothered me. Still does.

Then we drove down to Wadi Rum, and enjoyed the desert scenery. Jordan's deserts are not of the cookie-cutter variety. In fact, I suspect that – at least in the western areas – you could take a Jordanian blindfolded anywhere among these deserts, and find upon removing the blindfold that she or he could pinpoint the location within about 50 km based merely on the topography and color of the sand. I really wish I had realized this from the start, so I could have gotten a few pictures to showcase the amazing specificity of the desert landscapes.

Approaching

One of the highlights in our trip planning had been arranging to spend the night in a desert camp in Wadi Rum, and this was the night that we had planned it. So we were concerned at having gone from slightly early to very late, and raced from Deesih to Rum. One amusing anecdote arose when I called Saleem, the camp leader, on Billy's cell phone to let him know we were running behind: I mispronounced Deesih as "Diseeh"; Saleem heard this as "the sea" and thought we had overshot Rum substantially and landed in Aqaba on the Red Sea. He was relieved that we were only 15 km off course. And, fortunately, he was not upset – and said that helping a Bedouin family was a good excuse.

We left the rental car in Rum as Saleem sent us to camp with one of his compatriots in a desert-capable Land Cruiser. Saleem held back, waiting for another group that was due to arrive.

|

Traveling to the camp involved driving to the southern edge of the gridlike arrangement of Rum, and then literally driving off the edge of the town into the untamed desert. |

To put that in perspective, here's a satellite view of where the road ends in the village of Rum:

|

| Satellite View of Rum |

We explored the camp, and then a short time later Saleem arrived with the other group: a family from Strassbourg, with whom I enjoyed chatting in French.

In the camp, we ate mensaf (delicious lamb, rice, and bread) and drank tea under a nearly full moon (which really helped in finding the bathroom about 50 meters from the tent). We shared an awkward moment at dinner when the French father asked whether they were still called "freedom fries" in America. (For those who have forgotten this particular debacle: Back when the Iraq War didn't seem like an unmitigated disaster, cooler heads prevailed in France. To punish France for its independence, government-run cafeterias in the U.S. renamed "French fries" as "freedom fries." The French embassy wisely limited its response, offering but two simple observations: (1) "We are at a very serious moment dealing with very serious issues and we are not focusing on the name you give to potatoes," and (2) French fries come from Belgium.)

Throughout the trip Billy and I found it easy to bond with the Europeans and Middle Easterners that we met by playing on our mutual distaste for American foreign policy under the Bush administration. And I took the opportunity to ask the folks here if they ever met Americans who supported Bush, either while traveling or at home in Strassbourg. Their response: "Actually, we've never met anyone who supports him." This is when it struck me why people like Americans (thank goodness) even though they hate America: because (generally) only the good Americans travel. The country may be divided into blue states and red states, but the passports all are blue. (Well, except the ones used by officials; those are red.)

|

So night fell, and everyone repaired to their respective rooms in the tents – except for the Bedouin, who slept in the open air.

I wasn't sleepy yet, and went to sit in the quiet moonlit grandeur of Wadi Rum and prepare the draft for this report. It took a while to catalog the pictures and summarize this very busy day, but I finally closed with the following (unedited) paragraph, which still brings me a flood of fond memories:

Sat on a rock, looking out at moonlit Wadi Rum, to write this first draft – but it's about 10:00 and the night chill is starting to descend, so I'm retreating to my tent.

| Main | ||||||||

| 20 | κʹ | |||||||

| 21 | καʹ | |||||||

| 22 | κβʹ | |||||||

| 23 | κγʹ | |||||||

| 24 | κδʹ | |||||||

| 25 | κεʹ | |||||||

| 26 | ח׳ | |||||||

| 27 | ט׳ | |||||||

| 28 | Previous | الأخير | ١٠ | |||||

| 29 | ١١ | |||||||

| 30 | Next | التالي | ١٢ | |||||

| 1 | ١٣ | |||||||

| 2 | ١٤ | |||||||

| 3 | ١٥ | |||||||

| 4 | ١٦ | |||||||

| 5 | ١٧ | |||||||

| 6 | ١٨ | |||||||