|

|

|

20 |

|

٢ |

|

| 21 |

|

٣ |

| 22 |

|

٤ |

| 23 |

|

٥ |

| 24 |

|

٦ |

| 25 |

|

٧ |

| 26 |

|

٨ |

| 27 |

|

٩ |

| 28 |

● |

١٠ |

| 29 |

|

١١ |

| 30 |

|

١٢ |

|

1 |

|

١٣ |

| 2 |

|

١٤ |

| 3 |

|

١٥ |

| 4 |

|

١٦ |

| 5 |

|

١٧ |

| 6 |

|

١٨ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| The Most Difficult Border Crossing |

Reluctantly having decided to skip Bethlehem because of the logistical challenge, we caught our early taxi across the West Bank to the closest crossing between Israel and Jordan. I was surprised by the squalor of the Palestinian settlements. And I must acknowledge that I was put off by the contrast with an audacious settlement near Jericho – a community that was obviously well-off and obviously Jewish (per the several Israeli flags on large poles). It was so garish that if I didn't know that it was an in-your-face political statement, I would have thought it was an outlet mall.

| EN |

West Bank |

| HE |

הגדה המערבית |

| AR |

الضفة الغربية |

Governed under an interim agreement by:

|

|

But one thing I didn't see, and was surprised not to see, was the Wall, or, officially, the EN Israeli West Bank barrier HE גדר ההפרדה . It shows up on maps in the areas that we traveled – but either I missed it, or it has not yet been constructed in these areas. We certainly didn't pass through any checkpoints until we got to the crossing zone.

This crossing itself is a contentious bridge over the Jordan River that the Israelis call the EN Allenby Bridge HE גשר אלנבי , the Jordanians call the EN King Hussein Bridge AR جسر الملك حسين , and the Palestinians call the EN al-Karameh Bridge AR جسر الكرامة . This place has a reputation as one of the most difficult border crossings in the world (yet it's probably easier than going between the Koreas). It wasn't as terrible as I had heard – but it was certainly tedious, and required advance planning: If we were crossing at either of the other two border stations between these countries, we could have purchased our Jordanian visas that same day, but because we were entering from the West Bank, over which Jordan doesn't recognize Israel's claim (even though it has relinquished its own claim), that option was not available here. For this reason, I had secured our visas from the Jordanian Embassy in Washington a few months before the trip began.

We got to the Allenby Bridge crossing a half hour before it opened, but were unable to enter for over an hour – so long, in fact, that our cab driver had to negotiate with another driver to take us from the first checkpoint to the terminal, so he could make an appointment back in Jerusalem. Another person waiting, who had made the crossing several times, said she had never seen it so bad. Part of the delay was that five busloads of Israeli Arabs were going to Saudi Arabia to perform EN umrah AR عمرة (a pilgrimage to Makkah at a time other than the Hajj), and were being processed first because they were Israeli citizens. I was glad to see that they were being treated fairly, which made the wait less onerous.

Even with that delay, the entire process took less than two-and-a-half hours, which is close to a best case scenario. The flow is a bit convoluted and bureaucratic on both the Israeli and Jordanian sides:

- Arrive at the first checkpoint.

- Wait in line to approach the checkpoint.

- Show your passport to enter the Allenby Bridge area.

- Receive a ticket (the driver in our case, not us) allowing approach to the terminal.

- Arrive at the second checkpoint (about 2 km).

- Wait in line to approach the checkpoint.

- Present the ticket received at the first checkpoint.

- Approach the terminal (about 200 m).

- Give the luggage to an employee, who puts it aside.

- Walk through an open-air metal detector to approach the terminal and enter the Departures Hall.

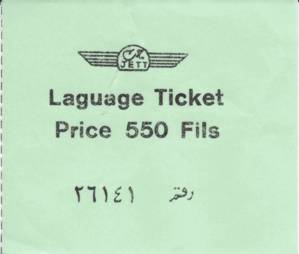

- Pay (all simultaneously) the Israeli exit tax, the luggage fee, and the bus transport fee.

- Go through passport control and show the exit tax receipt.

- Exit the building

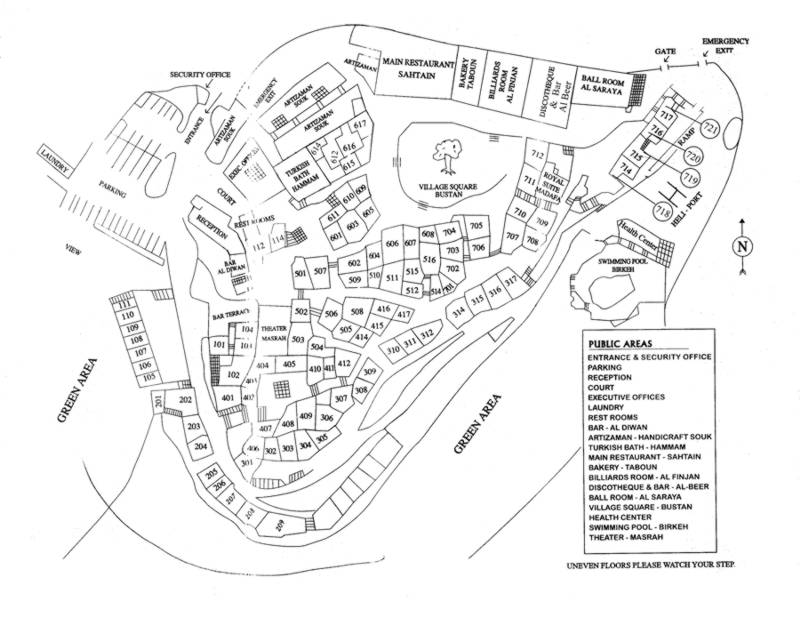

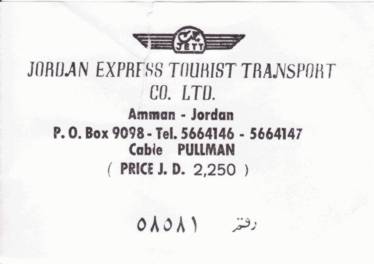

- Point to nearby waiting luggage so it can be placed on a Jordan Express Tourist Transport (JETT) bus.

- Wait for the bus driver to get departure approval from the Israeli authorities.

- Ride over the bridge.

- Arrive at a stop on the Jordanian side (about 2 km)

- Relinquish passport to a guard, who reviews it and and hands it to the bus driver for safekeeping.

- Arrive at the Jordanian terminal (about 3 km).

- Exit the bus and walk into the terminal

- Wait for luggage to be unloaded from the bus.

- Approach the scanner as your luggage is being placed through it by the Jordanian authorities.

- Retrieve luggage after scanning.

- Walk (with luggage) to the right of two side-by-side windows (because Arabic is read right-to-left, this is probably intuitive to the Jordanians, but it felt backward to us – more so because we were approaching the windows from the left).

- Identify the passport by nationality and name.

- Wait while the employee visually confirms your identity.

- Wait while the passport is passed, behind the glass, to the left of the side-by-side windows

- Wait while the passport is processed.

- Listen for your name to be called at the left window.

- Retrieve the passport.

- Enter the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan.

Even with the tedium, I found the employees genial and welcoming. One, in particular, at Israeli passport control, was excited to notice the Guatemalan stamps in my passport. She said, "You've been to Guatemala? I'm from there!"

| The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan |

| EN |

Jordan |

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan |

| AR |

الأردن |

المملكة الأردنية الهاشمية |

|

|

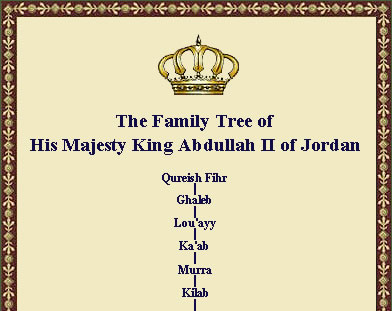

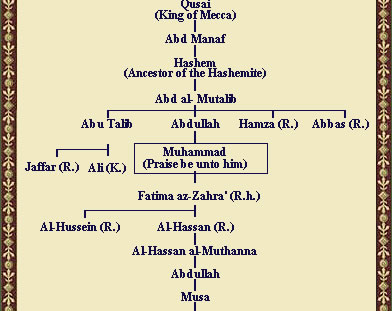

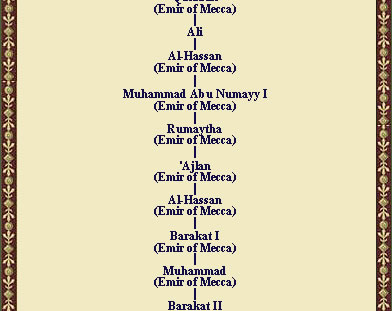

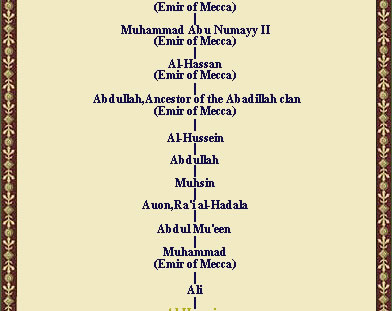

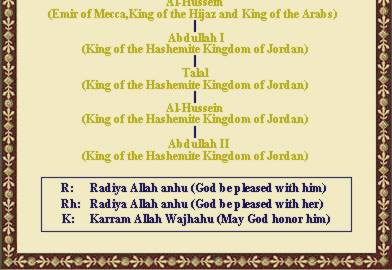

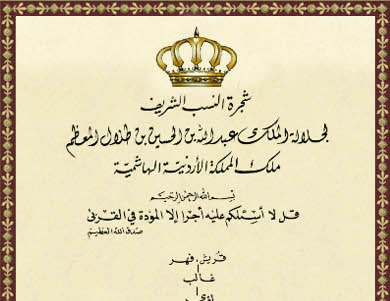

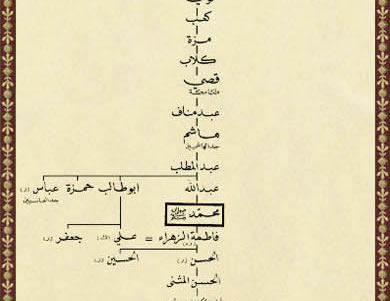

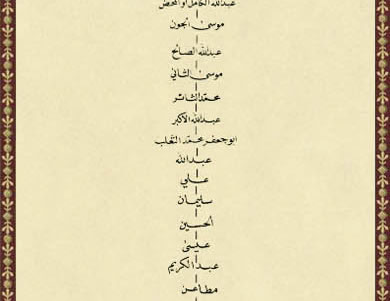

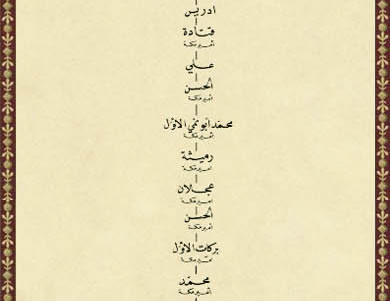

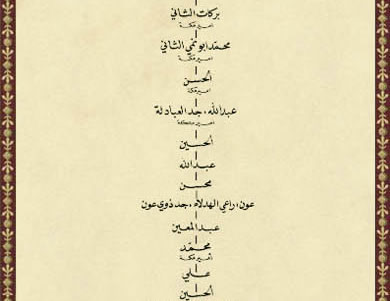

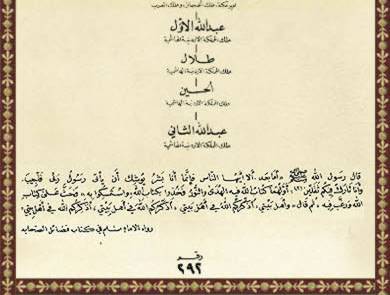

Now you may be thinking, how does a "Hashemite kingdom" differ from all of those other kingdoms I'm used to. The answer is that "Hashemite" simply refers to an auspicious lineage, not the style of governance. The Hashemites trace their heritage to EN Hashim ibn Abd Manaf AR هاشم بن عبد مناف , the great grandfather of EN Muhammad AR محمد , although the term today is generally applied to descendents of Muhammad's daughter, EN Fatimah az-Zahra AR فاطمة الزهراء . And if this leads you to wonder what the family tree of the King of Jordan looks like, well who am I to disappoint you?

We found the agent from Reliable Rent-a-Car at the terminal as promised and picked up the car without difficulty. It was a Toyota Corolla – not exotic, but dependable. We found the agent from Reliable Rent-a-Car at the terminal as promised and picked up the car without difficulty. It was a Toyota Corolla – not exotic, but dependable.

There was no ATM at the border village, but I found one in the town just up the way, and was able to load up on the Jordanian EN dinar AR دينار . This is a fun currency in that it's divided, not into hundredths like everything else I've ever used, but thousandths. More accurately, it is divided into 10 EN dirham AR درهم , into 100 piasters or EN qirsh AR قرش , or into 1,000 EN fils AR فلس , although in practice, dirham and fils are not widely used in spoken references; written amounts invariably extend to the third decimal (fils).

The Jordanian Dinar

JOD (JD or D) |

|

|

1.000 JD

|

|

5.000 JD

|

|

10.000 JD

|

|

20.000 JD

|

|

50.000 JD

|

|

So with money in hand, I got on the Dead Sea Highway and headed south, and almost found an opportunity to spend my withdrawal: I was stopped in the first half hour for going 96 in an 80 km/h zone – but let off with a warning and a "Welcome to Jordan." The Jordanians around me were cruising at much higher speeds – but either they knew when to hit the brakes, or they are not held to the same standard. (Considering how the U.S. treats foreigners, I am hardly in a position to criticize the latter potentiality.) Either is plausible: Jordanian rental cars have a distinctive green tag and can be recognized at quite a distance. We eventually realized that this is why people were shouting "Welcome to Jordan!" from the sidewalks whenever we passed.

We heard "Welcome to Jordan" more times than we could count and began to think they should consider printing it on their money. They take the hospitality thing (and the tourist bucks it brings) seriously here. Interestingly, there was another slogan that was almost as common, but this one we only saw in writing (on placards in almost every shop), and only in Arabic: AR «الأردن اول» ; it means EN "Jordan First."

But they're a patriotic folk. If you travel enough, you see major differences in how various nations display their emblems. I don't recall ever seeing the Swiss flag in Switzerland, and not too often in most of the European countries; not much in Belize; a lot in Guatemala. In the U.S., of course, some communities battle over which can fly the most or largest flags. But Jordan is over the top: The Jordanian flag is everywhere.

|

The Jordanian Flag |

Driving in Jordan is interesting. The country's highway system is very well-conceived, with clear lane markings, wide shoulders in most places, appropriate and well-marked no-passing zones, truck lanes on steep hills, separate car/truck speed limits, and good signage. The truck drivers are sticklers, but for the car drivers none of the above is more than a nagging suggestion. It seems as if some Jordanian official went to Europe, saw how it was done, reproduced the system, and then unveiled it without explanation to a people accustomed to finding their own routes through the desert.

The style of passing distresses most Americans, but I was already familiar with it from other places: The two-lane roads are easily wide enough for three cars, so all you have to do to pass is (1) make sure nothing is coming down the middle in the other direction and (2) aim for the center line. The cars on both sides will squeeze to the curb and make room – so you don't have to wait for a break in oncoming traffic.

But the oddest thing was that when the road was empty, Jordanians had a strange habit driving on the wrong side even when there was no clear advantage to doing so: Not only would they cross the center line to straighten a curve or avoid an obstacle; sometimes they would cross it for no discernable reason whatsoever. On more than one occasion (and at least once on a long, straight, smooth road) I found a Jordanian driver coming toward me in my lane, only switching to the proper side of the road when I came into view.

So with Jordan finally came the day that I was immersed in Arabic. I had lots of opportunity to speak it in Jerusalem (and a little bit in the airports in Athens and Larnaca), but Jordan was the real deal.

Just about everyone reading this knows that I have been studying EN Arabic AR اللغة العربية for over a year in preparation for this trip. It may seem like an absurd investment for a two-week vacation (only about half of which was spent in Arabic-speaking countries) – but it has, in fact, been one of the most rewarding endeavors of my life. Scholars of my life (if any) know that learning novel ways of accomplishing familiar tasks is one of the things I find most exciting – and has guided my life and my travels more, perhaps, than I should have allowed, viz.:

- The first international trip Billy and I took could have been anywhere, but it was to Britain in large part because I wanted to drive on the left.

- The logistical challenge of a city built on water compelled me toward Venice from the childhood day that I first heard of it until I crossed the Venetian Causeway on September 18, 2003.

- Many of our hotels have been selected entirely because of their departure from the norm – both on previous trips (haunted castle in Inverness; cliffside rooms in Sorrento; mountaintop observatory in Gornergrat; hanging beds in Puerto Morelos; treehouse in San Ignacio) and on this one (cave in Santorini, Bedouin village [today], desert camp [tomorrow]).

- One of my favorite thing about the Italy trips was learning about the unusual addressing systems in some cities: (1) the overlapping, color-coded system of addresses in Florence; (2) the random incrementation of street numbers within the sestieri of Venice.

Even more mundane fascinations – using chopsticks; driving a manual transmission vehicle; counting on an abacus; sleeping on a waterbed – hark back to this obsession with the unfamiliar familiar.

I like to think that these areas of interest have broadened my mind in ways that will serve me well both socially and personally. But let me tell you: Broadening the mind can have its unintended consequences: I fervently hope – and believe! – that the upside will outweigh the downside, like protecting me from Alzheimer's (AR ان شاء الله AR in sha' Allah ). But sometimes, conversely, it just makes me feel stupid. Take – just for example – stapling: Prior to learning Arabic, I never questioned that a staple went on the top-left corner of a page; it was as natural as unscrewing a lid counter-clockwise. But now, with Arabic, I actually have to bring a thought process into the simple act of stapling paper, with the obvious consequent milliseconds of delay as I consciously consider, "Is this an English top-left page, or is this an Arabic top-right page?"

But even so, I'm glad I embarked on this journey (the language one as well as the airplane one): Arabic is an utterly ideal pursuit for me: I came into it fascinated by the right-to-left style, cursive script, and malleable letter forms. And every shred of grammar I have learned since then has furthered my appreciation for this exquisitely elegant tongue. Really, after a bit of study, Arabic leaves one with the impression of a complexly fabricated language. Like those elegant calligraphic images – such a cornerstone of Arabic culture – which appear so knotted and impenetrable as to be unreadable, but which are in fact to the trained eye a viable style of writing, the language itself seems so intricate that it would lose its ability to serve as a vehicle of communication in the face of the complex beauty of its structure. Yet it succeeds, even shines. Some Muslims believe that Arabic is the language of God – and it is not for nothing that they hold this view.

For those who are interested, I'll do my best to highlight some of the most fascinating aspects of Arabic – without, I promise, actually teaching you anything. (I've done my best to make this interesting, and I think you'll enjoy it – but you should be forewarned that this does go on for a while; if you just can't stand being away from the pictures for too long, you can click here to skip down past this exploration of Arabic. [But you'll miss the seals and armadillos.])

| ا |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

Final |

|

Medial |

|

Initial |

|

Isolation |

| |

ـى or ـا |

|

ى or ا |

| |

ـب |

|

ـبـ |

|

بـ |

|

ب |

| |

ـة or ـت |

|

ـتـ |

|

تـ |

|

ة or ت |

| |

ـث |

|

ـثـ |

|

ثـ |

|

ث |

| |

ـج |

|

ـجـ |

|

جـ |

|

ج |

| |

ـح |

|

ـحـ |

|

حـ |

|

ح |

| |

ـخ |

|

ـخـ |

|

خـ |

|

خ |

| |

ـد |

|

د |

| |

ـذ |

|

ذ |

| |

ـر |

|

ر |

| |

ـز |

|

ز |

| |

ـس |

|

ـسـ |

|

سـ |

|

س |

| |

ـش |

|

ـشـ |

|

شـ |

|

ش |

| |

ـص |

|

ـصـ |

|

صـ |

|

ص |

| |

ـض |

|

ـضـ |

|

ضـ |

|

ض |

| |

ـط |

|

ـطـ |

|

طـ |

|

ط |

| |

ـظ |

|

ـظـ |

|

ظـ |

|

ظ |

| |

ـع |

|

ـعـ |

|

عـ |

|

ع |

| |

ـغ |

|

ـغـ |

|

غـ |

|

غ |

| |

ـف |

|

ـفـ |

|

فـ |

|

ف |

| |

ـق |

|

ـقـ |

|

قـ |

|

ق |

| |

ـك |

|

ـكـ |

|

كـ |

|

ك |

| |

ـل |

|

ـلـ |

|

لـ |

|

ل |

| |

ـم |

|

ـمـ |

|

مـ |

|

م |

| |

ـن |

|

ـنـ |

|

نـ |

|

ن |

| |

ـه |

|

ـهـ |

|

هـ |

|

ه |

| |

ـو |

|

و |

| |

ـي |

|

ـيـ |

|

يـ |

|

ي |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

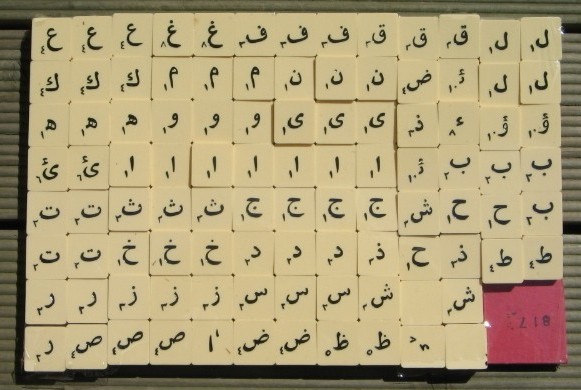

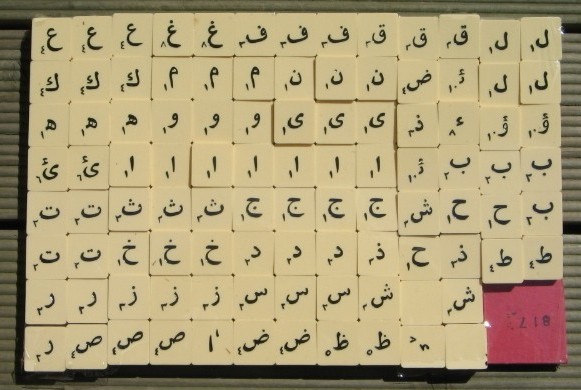

In fairness, I can't complain about the letters. As I've already disclosed above, it was Arabic script that drew me in. But they are a beast to keep track of for the beginning student: These 28 letters are derived from 86 different forms reflecting embellishments (dots and tails, essentially) on (let's say) 21 basic shapes.

And each letter can have as many as four different forms, depending on whether it is initial, medial, final, or isolated.

And even more galling than that is that handwritten Arabic contains variations independent of printed Arabic:

- In print the dots are separate, but in handwriting two dots are often written as a line, and three dots are often written as a caret. This makes writing easier, and is inoffensive. But more vexingly: In print the characters flow on the line from right-to-left, while in proper handwriting many of the letters are stacked vertically. Compare these printed (unboxed) and handwritten (boxed) versions:

- The medial form of the character ـهـ looks much like a figure-eight. But in handwriting it is often made with a simple downward point. Compare:

- The character ـسـ (shown here in its medial form) is printed with three unevenly spaced ridges. But in handwriting, it is just a straight line. But ... but ... but ... if you see a long straight line in printed text, it's not the ـسـ; rather, it's just irrelevant spacing for the aesthetics of the printing. Compare the printed (unboxed) and handwritten (boxed) versions below (everything in black is the same word; everything in blue is the same word):

| These are the same |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

حساب |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

These are different |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

حــــاب |

|

|

|

|

|

حاب |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

These are the same |

And it gets challenging – especially in the first weeks – remembering all the details: the four different shapes of هـ; when to write ة, instead of ت; remembering that the final loops for ن, ل, ق, ض, ص, ش, س, and ي swing low, while those for ث, ت, ب, and ف do not. Some letters cut you a break: ط and ظ are the same in all four forms, but what they relinquish in ease of writing they take back in difficulty of pronunciation (see below).

But still, the writing is a sheer joy to me: It's beautiful to look at. And, to be completely honest, it makes me feel smart when I write it. With Cyrillic (which, to be fair, I don't know at all) or Greek (which I only know a little), you're just using a different code. But with Arabic, you're using an entirely different thought process. Moreover, Arabic can't be written without it. I'll confess to a naïve belief earlier in my studies that perhaps it would be better simply to write Arabic in Latin characters, but this would not open Arabic up; rather it would make the linguistic relationship between the words impenetrable. Nonetheless, several systems of transliteration have been developed:

| Arabic |

|

|

SATTS

(US Military) |

|

Library of

Congress |

|

ISO |

|

Qalam |

|

SAS |

|

SM |

|

IPA |

|

Arabic Chat

(IM) |

|

| ء |

|

|

E |

|

ʼ, – |

|

ˈ, ˌ |

|

' |

|

ʾ |

|

' |

|

ʔ |

|

2 |

|

| ا |

|

|

A |

|

ā |

|

ʾ |

|

aa |

|

a, i, u, ā |

|

aa |

|

aː |

|

a |

|

| ب |

|

|

B |

|

b |

|

b |

|

b |

|

b |

|

b |

|

b |

|

b |

|

| ت |

|

|

T |

|

t |

|

t |

|

t |

|

t |

|

t |

|

t |

|

t |

|

| ث |

|

|

C |

|

th |

|

ṯ |

|

th |

|

ṯ |

|

ç |

|

θ |

|

s, th |

|

| ج |

|

|

J |

|

j |

|

ǧ |

|

j |

|

ŷ |

|

j |

|

ʒ |

|

g, j |

|

| ح |

|

|

H |

|

ḥ |

|

ḥ |

|

H |

|

ḥ |

|

ḥ |

|

ħ |

|

7 |

|

| خ |

|

|

O |

|

kh |

|

ẖ |

|

kh |

|

j |

|

x |

|

x |

|

5, 7', kh |

|

| د |

|

|

D |

|

d |

|

d |

|

d |

|

d |

|

d |

|

d |

|

d |

|

| ذ |

|

|

Z |

|

dh |

|

ḏ |

|

dh |

|

ḏ |

|

đ |

|

ð |

|

z, th |

|

| ر |

|

|

R |

|

r |

|

r |

|

r |

|

r |

|

r |

|

r |

|

r |

|

| ز |

|

|

; |

|

z |

|

z |

|

z |

|

z |

|

z |

|

z |

|

z |

|

| س |

|

|

S |

|

s |

|

s |

|

s |

|

s |

|

s |

|

s |

|

s |

|

| ش |

|

|

|

|

sh |

|

š |

|

sh |

|

š |

|

š |

|

ʃ |

|

sh |

|

| ص |

|

|

: |

|

ṣ |

|

ṣ |

|

S |

|

ṣ |

|

ṣ |

|

sˁ |

|

S, 9 |

|

| ض |

|

|

X |

|

ḍ |

|

ḍ |

|

D |

|

ḍ |

|

ḍ |

|

dˁ |

|

D, 9' |

|

| ط |

|

|

U |

|

ṭ |

|

ṭ |

|

T |

|

ṭ |

|

ṭ |

|

tˁ |

|

TH, T, 6 |

|

| ظ |

|

|

Y |

|

ẓ |

|

ẓ |

|

Z |

|

ẓ |

|

đ̣ |

|

ðˁ |

|

Z, TH, 6' |

|

| ع |

|

|

` |

|

ʻ |

|

ʿ |

|

` |

|

ʿ |

|

ř |

|

ʕ |

|

3 |

|

| غ |

|

|

G |

|

gh |

|

ġ |

|

gh |

|

g |

|

ğ |

|

ɣ |

|

gh, 3' |

|

| ف |

|

|

F |

|

f |

|

f |

|

f |

|

f |

|

f |

|

f |

|

f, ph |

|

| ق |

|

|

Q |

|

q |

|

q |

|

q |

|

q |

|

q |

|

q |

|

q, 8 |

|

| ك |

|

|

K |

|

k |

|

k |

|

k |

|

k |

|

k |

|

k |

|

k |

|

| ل |

|

|

L |

|

l |

|

l |

|

l |

|

l |

|

l |

|

l , lˁ |

|

l |

|

| م |

|

|

M |

|

m |

|

m |

|

m |

|

m |

|

m |

|

m |

|

m |

|

| ن |

|

|

N |

|

n |

|

n |

|

n |

|

n |

|

n |

|

n |

|

n |

|

| هـ |

|

|

~ |

|

h |

|

h |

|

h |

|

h |

|

h |

|

h |

|

h |

|

| و |

|

|

W |

|

w |

|

w |

|

w |

|

w, ū |

|

w, o |

|

w , uː |

|

w |

|

| ي |

|

|

I |

|

y |

|

y |

|

y |

|

y, ī |

|

y, e |

|

j , iː |

|

i, y |

|

| آ |

|

|

AEA |

|

ā |

|

ʾâ |

|

~aa |

|

ā |

|

'aa |

|

ʔaː |

|

a |

|

| ة |

|

|

@ |

|

h, t |

|

ẗ |

|

h, t |

|

t, – |

|

ŧ |

|

a, at |

|

t, – |

|

| ى |

|

|

/ |

|

y |

|

ỳ |

|

ae |

|

à |

|

à |

|

aː |

|

a |

|

The problem is: These are all a failure. SATTS makes punctuation impossible because punctuation marks are included. Many of the others include obscure characters that can only be viewed on computers with a full Unicode font set (if you don't see any boxes above, you have a very well-trained computer). Others make you guess as to the original text and thus as to the pronunciation (e.g., Is "sh" in Qalam transcription one letter or two?). And if they allow vowel additions (all except SATTS and Arabic Chat), how are the vowels and other diacritical marks encoded? Just to understand the scope of the problem, look at the familiar name, Omar Khayyam, which speakers of Arabic know to be written as عمر خيام:

| |

|

unvocalized |

|

vocalized |

Arabic |

|

عمر خيام |

|

عُمَر خَيام |

SATTS (US Military) |

|

`MR OIAM |

|

|

Library of Congress |

|

ʻmr khyām |

|

ʻumar khayyām |

ISO |

|

ʿmr ẖyʾm |

|

ʿumar ẖayyʾm |

Qalam |

|

`mr khyaam |

|

`umar khayyaam |

SAS |

|

ʿmr jyām |

|

ʿumar jayyām |

SM |

|

řmr xyaam |

|

řumar xayyaam |

IPA |

|

|

|

ʕumar xajjaːm |

| Arabic Chat (IM) |

|

3mr 7'yam |

|

|

In my opinion, the best is the least scientific: Arabic Chat (those clever kids!). But we're still left with the fact that none of these systems really works. The more useful they are in helping a non-speaker of Arabic, the less reliability they have with a one-to-one (and, thus, easily reversible) correlation to the original text. If English didn't have so many sounds that don't have letters (th as in "think"; th as in "that"; sh), or if Arabic didn't have so many sounds that English represents with a single letter (notably, the emphatic consonants; see below), then a precise correlation (at least between English and Arabic) might be possible. But it was not to be. So we are left with "Omar Khayyam" (in English, that is; the Germans are left with "Omar Chajjam" to refer to the same guy). (His full name, by the way, is غیاث الدین ابو الفتح عمر بن ابراهیم خیام نیشابوری; transliterate that!) (N.B.: In this document I have not been consistent in my use of transliteration; this is in part because I got my base information from different sources that used different systems; but I did not go back through and bring order to it because in some areas a consistent system would actually decrease readability for the casual [non-Arabic speaking] reader.)

John Wilkins didn't care for the writing though. More on him anon – but for now, he wrote in his seminal work, An Essay towards a Real Character and a Philosophical Language: "The Arabic character, though it showed beautiful, yet is it too elaborate, and takes up too much room, and cannot dwell the written small." He shows his ignorance: Arabic is one of the most compact systems of writing ever devised, and takes up significantly less space, for the same conceptual material, than English.

So very early on, I diverged from John Wilkins and made my peace with the Arabic letters. So much of a peace, in fact, that I learned to type them, and then learned them in the Arabic manual alphabet:

Arabic Keyboard:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

backspace |

| tab |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| caps lock |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

enter |

| shift |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

shift |

Arabic Fingerspelling:

| ض |

ص |

ش |

س |

ز |

ر |

ذ |

د |

خ |

ح |

ج |

ث |

ت |

ب |

ا |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ة

|

|

ى

|

|

| |

| ء |

ي |

و |

هـ |

ن |

م |

ل |

ك |

ق |

ف |

غ |

ع |

ظ |

ط |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| ب |

|

| |

|

| |

For reasons related to Qur'anic transcription and local pronunciation in early Islamic times, the hamza was not included in the character set of the Arabic alphabet, yet it is integral to the writing of the language now. Essentially, it represents a "glottal stop," which is the sound between the two syllables of "uh-oh." Perhaps because it is an add-on to the alphabet, it is treated oddly, like a full letter in some instances, and like a diacritical mark in others. Following are examples of its shape:

| alif madda |

hamzat al-waSl |

above yaa |

above waw |

below alif |

above alif |

on the line |

|

|

| ئ |

|

ـئـ |

| final/isolated |

|

medial |

|

|

|

|

|

The rules governing which of these characters to use, and when, are a mixture of "complex" and "maddening":

- If the hamza is initial:

- It is always written on an ا – over it (أ) if the following sound is ـَـ or ـُـ /و; under it (إ) if the following sound is ـِـ /ي (this is the only situation in which a hamza is written under the alif).

- If ا follows, alif-madda (آ) will occur.

- If the alif is elided, hamzat al-waSl (ٱ) will occur (but only in fully vocalized texts).

- If the hamza is medial:

- If a long vowel or diphthong precedes, the seat of the hamza is determined mostly by what follows:

- If ـِـ /ي or ـُـ /و follows, the hamza is written over ي or و, accordingly.

- Otherwise, the hamza is generally written on the line (ء), except ...

- If a ي precedes this would conflict with the stroke joining the yaa to the following letter, so the hamza may be written over ي (i.e., ـئـ).

- Otherwise, both preceding and following vowels have an effect on the hamza.

- If there is only one vowel (or two of the same kind), the hamza is written over the corresponding seat (و, ا, or ي).

- If there are two conflicting vowels, ـِـ /ي takes precedence over ـُـ /و; ـُـ /و over ـَـ /ا.

- If the hamza appears over the ا, and a ا follows, alif-madda (آ) will occur.

- If the hamza is final:

- If a short vowel precedes, the hamza is written over the letter (و, ا, or ي) corresponding to the short vowel.

- Otherwise (i.e. long vowel, diphthong or consonant preceding), the hamza is written on the line (ء).

|

| ج |

The Vowels and Diacriticals

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

There are but three vowels in Arabic, but the language manages to bring some extraordinary complexity with these three phonemes:

- As in English, vowels/syllables may be stressed or unstressed.

- Unrelated to stress, vowels may be short (as are all English vowels) or long (about twice as long in duration as a short vowel). The long vowels are written in their consonantal forms; the short vowels are diacritical marks above or below the letter:

| long |

|

ا |

|

و |

|

ي |

| |

alif |

|

waw |

|

ya' |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| short |

|

ـَـ |

|

ـُـ |

|

ـِـ |

| |

fatha |

|

Damma |

|

kasra |

- Vowels may be emphatic or regular, depending on the surrounding consonants. The most prominent such shift is with ا, which is normally pronounced like a as in "bat," but which shifts in emphatic pronunciation to a as in "father."

So for each of the three vowels, there are eight possible pronunciations (stressed-short-regular, stressed-short-emphatic, stressed-long-regular, stressed-long-emphatic, unstressed-short-regular, unstressed-short-emphatic, unstressed-long-regular, and unstressed-long-emphatic). But there is also a hierarchy among the vowels, which can affect orthography and pronunciation; it goes, from highest to lowest:

- ـِـ /ي

- ـُـ /و

- ـَـ /ا

And just a few other random things to make you scratch your head and feel thankful that you're not studying this language:

- The short vowels can be modified (more or less, doubled) at the end of a word to represent various declensions (tanween; see Chart 1 below).

- There is a diacritical mark (shadda; see Chart 2 below) to indicate that pronunciation of a consonant is doubled, and it can be modified to incorporate the various short vowels as needed (see Chart 1 below).

- An additional diacritical mark (sukkun; see Charts 1 and 2 below) merely represents that the consonant modified is not followed by a vowel.

- A largely unused version of ا (dagger alif; see Chart 2 below) exists only in fully vocalized texts, and is so uncommon that is doesn't even appear on the Arabic keyboard.

- No word in Arabic begins with a vowel. This seems like a simple fact, except that the first letter a student learns is the vowel ا, and a glance at any Arabic text reveals that a huge number of words begin with ا – just, for example, الله (Allah). This is because the ا at the beginning of the word isn't really an ا; rather, it is representative of the hamza, which is often omitted.

| Chart 1 |

|

Chart 2 |

| ـَـ |

|

ـُـ |

|

ـِـ |

|

ـٰـ |

| fatha |

|

Damma |

|

kasra |

|

dagger alif |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ـًـ |

|

ـٌـ |

|

ـٍـ |

|

ـْـ |

| fatha tanween |

|

Damma tanween |

|

kasra tanween |

|

sukkun |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ـَّـ |

|

ـُّـ |

|

ـِّـ |

|

ـّـ |

| shadda fatha |

|

shadda Damma |

|

shadda kasra |

|

shadda |

And note, further, that these can be stacked as much as the pronunciation of the word requires, as in the following example of a medial ي with a hamza, a shadda, and a Damma on it:

ـئُّـ

Anyway, to the beginning student, these vowels and other diacriticals are a mess. If the text if full of them, it is hard to read through all the distracting gloss. If they are omitted, then (with the student) pronunciation errors abound and some familiar words are difficult to recognize. In some contexts (including Microsoft Word, if it is so configured), they are written in a different color; this may help, but I haven't had a chance to read through unfamiliar text with this embellishment. I've always felt a particular sympathy for people who have to learn to read English as a foreign language, with our highly flexible spelling conventions, and I've wondered how I would do if faced with this challenge. Arabic has given me a chance to find out. (Answer: I do okay, but it's really, really hard.)

In fairness, people who are fluent in Arabic say that the lack of vowel marks and diacriticals is not an impediment, and the context makes things clear. In my (admittedly limited) experience, this is a dubious, but universal, assertion. I offer the following to illustrate my point:

| أنتَ |

|

means "you" (masculine) |

| |

|

and |

| أنتِ |

|

means "you" (feminine) |

| |

|

but without vowels,

they are both written as |

| أنت |

|

|

|

|

|

| يَدرُسَ |

|

means "he studies" |

| |

|

and |

| يُدَرِّسَ |

|

means "he teaches" |

| |

|

but without vowels,

they are both written as |

| يدرس |

|

|

|

| |

|

| د |

|

| |

|

| |

Arabic has evolved with a set of ligatures. Only one of them is mandatory (lem-alif, or لا), but it is essential for the student of Arabic to be familiar with them in general. A sampling of the forms is as follows:

| non-ligature |

همـ |

ممـ |

لمـ |

لحـ |

سمـ |

حمـ |

تمـ |

تحـ |

لـا |

| ligature |

همـ |

ممـ |

لمـ |

لحـ |

سمـ |

حمـ |

تمـ |

تحـ |

لا |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

mandatory |

|

| |

|

| هـ |

|

| |

|

| |

Arabic introduces a complex mixture of sounds, only some of which are familiar through English and romance languages. Particularly challenging at first are the ع and غ, the latter more confusing than necessary in that it is really the sound of the French r, but is generally transliterated as "gh." The emphatic consonants, too, provide a wealth of tooth-grinding frustration, not the least of which comes from the ض (Ḍād) a sound so rare that Arabic is sometimes called the "Language of the Ḍād," and so important that history records the mouth-shape by which Mohammed pronounced it (with both sides of his tongue).

The challenge of the emphatic consonants is that when you are listening to them side-by-side with their non-emphatic counterparts, it is obvious that there is a slight difference, but (1) in rapid speech it is hard for the student to shape and perceive the differences in these sounds and (2) because we lack a colloquial vocabulary to describe the motions inside the mouth, it is nearly impossible to describe how to form these sounds, viz. Wikipedia:

"Emphatic consonant is a term widely used in Semitic linguistics to describe one of a series of obstruent consonants which originally contrasted with series of both voiced and voiceless obstruents. In specific Semitic languages the members of this series may be realized as pharyngealized, velarized, ejective or plain voiced or voiceless consonants. ... In Arabic emphasis is synonymous with a secondary articulation involving retraction of the dorsum or root of the tongue, which has variously been described as velarization, uvularization or pharyngealization depending on where the locus of the retraction is assumed to be. Within Arabic, the emphatic consonants have been reported as varying in phonetic realization from dialect to dialect, but are typically realized as pharyngealized consonants."

Here's my best shot at putting that in plain language: Arabic has sounds very similar to the English T, D, TH (as in "this"), S, and L. But for each of these it also has an emphatic counterpart which is pronounced with the mouth narrowed and the tongue more flat against the roof. Of note, they are distinguished not only by their own distinct sounds, but also how they influence the pronunciation of surrounding vowels.

The emphatic L sound is particularly interesting, in that it occurs in only one single word of the Arabic language: الله ("Allah," so it's an important word, eh?). This would appear to be a particularly challenging phoneme if not for one little fact: The emphatic Arabic L is the sound made by the English L; for the regular non-emphatic L you just lower the tongue away from the roof of the mouth while keeping the tip against the teeth; it's easy to do – hard to remember to do, but easy to do.

If you want to know what those letters sound like, you can click on the names below. Unlike, for example, the English letters H and W (to pick the two most prominent of many examples), Arabic letters always begin with the sound they make.

It is the like-shaded letters that students (who are natives speakers of English) find hardest to distinguish from each other. The two gray-shaded letters are sounds that are completely unlike sounds in English.

Anyway, in case you were saying to yourself, "I wonder how the IPA chart compares English phonemes with Arabic," here's the answer:

| Place of articulation → |

Labial |

Coronal |

Dorsal |

Radical |

(none) |

| Manner of articulation ↓ |

Bilabial |

Labiodental |

Dental |

Alveolar |

Postalveolar |

Retroflex |

Palatal |

Velar |

Uvular |

Pharyngeal |

Epiglottal |

Glottal |

| Nasal |

|

m |

|

ɱ |

|

|

|

n |

|

|

|

ɳ |

|

ɲ |

|

ŋ |

|

ɴ |

|

| Plosive |

p |

b |

* |

* |

|

|

t |

d |

|

|

ʈ |

ɖ |

c |

ɟ |

k |

ɡ |

q |

ɢ |

|

ʡ |

ʔ |

|

| Fricative |

ɸ |

β |

f |

v |

θ |

ð |

s |

z |

ʃ |

ʒ |

ʂ |

ʐ |

ç |

ʝ |

x |

ɣ |

χ |

ʁ |

ħ |

ʕ |

ʜ |

ʢ |

h |

ɦ |

| Approximant |

|

β̞ |

|

ʋ |

|

|

|

ɹ |

|

|

|

ɻ |

|

j |

|

ɰ |

|

|

|

| Trill |

|

ʙ |

|

|

|

|

|

r |

|

|

|

* |

|

|

|

|

ʀ |

|

* |

|

| Tap or Flap |

|

ѵ̟† |

|

ѵ† |

|

|

|

ɾ |

|

|

|

ɽ |

|

|

|

|

|

* |

|

| Lateral Fricative |

|

|

|

ɬ |

ɮ |

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

| Lateral Approximant |

|

|

|

|

l |

|

|

|

ɭ |

|

ʎ |

|

ʟ |

|

|

| Lateral Flap |

|

|

|

|

ɺ |

|

|

|

* |

|

* |

|

* |

|

|

|

|

|

| ʍ |

Voiceless labialized velar approximant |

| w |

Voiced labialized velar approximant |

| ɥ |

Voiced labialized palatal approximant |

| ɕ |

Voiceless palatalized postalveolar (alveolo-palatal) fricative |

| ʑ |

Voiced palatalized postalveolar (alveolo-palatal) fricative |

| ɧ |

Voiceless "palatal-velar" fricative |

|

| Key |

|

| |

English Only |

| |

Arabic Only |

| |

Both |

| |

Both, but Arabic has emphatic and non-emphatic pronunciations |

|

|

And, just for instance, if you were thinking, "I wonder if those hard to pronounce letters would run up the score in a EN Scrabble AR سكرابل game," here's the answer: It's hit or miss.

This is all Classical Arabic, of course: On the street there is more variation as to pronunciation – especially with the letter ج, which can be pronounced like s in "measure" (zh), like j in "jeep," and like g in "go." And oddly, even though this is pretty straightforward, they don't readily understand the other versions: I learned to pronounce EN university AR جامعة as AR zhami'a , but in Egypt, where it's pronounced AR gami'a they typically didn't understand me until I modified my pronunciation.

But even in Classical Arabic there is untidiness, with the most notable example being the "sun letters" and "moon letters": Sun letters are those which cause the L sound in the definite article to be elided, and cause no end of difficulty in transliteration. In all of the examples below, the word preceding the hyphen would be written the same in Arabic: الـ; it stays as "al-" with the moon letters, but transforms to mimic and double the following consonant with the sun letters.

| |

Moon Letters

الخروف القمرية |

|

|

Sun Letters

الحروف الشمسية |

|

| |

al-' |

|

ا |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-b |

|

ب |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ت |

|

at-t |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ث |

|

ath-th |

|

| |

al-j |

|

ج |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-H |

|

ح |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-kh |

|

خ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

د |

|

ad-d |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ذ |

|

aTH-TH |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ر |

|

ar-r |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ز |

|

az-z |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

س |

|

as-s |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ش |

|

ash-sh |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ص |

|

aS-S |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ض |

|

aD-D |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ط |

|

aT-T |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ظ |

|

aZ-Z |

|

| |

al-` |

|

ع |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-gh |

|

غ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-f |

|

ف |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-q |

|

ق |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-k |

|

ك |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ل |

|

al-l |

|

| |

al-m |

|

م |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

ن |

|

an-n |

|

| |

al-h |

|

هـ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-w |

|

و |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

al-y |

|

ي |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| و |

|

| |

|

| |

A regular sequence of letters is used for ordinary alphabetization, but in lists that are preceded by letters, the same twenty-eight characters are arranged in an entirely different sequence. Headings in this list of Arabic attributes, you may notice, are prefixed in the abjad sequence.

Both sequences are shown below. On the standard sequence, the shading from white to yellow increases incrementally. You can compare the unchanged shading of the letters in the abjad sequence to see how thoroughly shuffled they are. Indeed, it is exactly as if English kept its regular sequence for the dictionary, but prefixed lists in the following order: A, B, E, H, Z, AA, K, F, P, AB, V, W, X, Y, L, R, T, N, U, J, M, C, D, G, I, O, Q, S ("AA" and "AB" to compensate for the fact that Arabic has 28 letters).

| Standard Sequence |

Position in ... |

| 28 |

27 |

26 |

25 |

24 |

23 |

22 |

21 |

20 |

19 |

18 |

17 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

Standard Sequence |

| ي |

و |

هـ |

ن |

م |

ل |

ك |

ق |

ف |

غ |

ع |

ظ |

ط |

ض |

ص |

ش |

س |

ز |

ر |

ذ |

د |

خ |

ح |

ج |

ث |

ت |

ب |

ا |

|

| |

|

| Abjad Sequence |

Position in ... |

| 28 |

27 |

26 |

25 |

24 |

23 |

22 |

21 |

20 |

19 |

18 |

17 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

13 |

12 |

11 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

Abjad Sequence |

| 19 |

17 |

15 |

9 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

13 |

10 |

21 |

14 |

20 |

18 |

12 |

25 |

24 |

23 |

22 |

28 |

16 |

6 |

11 |

27 |

26 |

8 |

5 |

2 |

1 |

Standard Sequence |

| غ |

ظ |

ض |

ذ |

خ |

ث |

ت |

ش |

ر |

ق |

ص |

ف |

ع |

س |

ن |

م |

ل |

ك |

ي |

ط |

ح |

ز |

و |

هـ |

د |

ج |

ب |

ا |

|

|

|

| |

|

| ز |

|

| |

|

| |

First, let us clear up the nomenclature: In English, we do not write with Arabic numerals, no matter what your fourth-grade teacher told you. The confusion arises because we use "Arabic numeration" – that is to say, we organize our numbers in columns of units, tens, hundreds, thousands, etc. But the characters we write with are best called "European numerals," though "Hindu-Arabic numerals" will suffice, as will "Western Arabic numerals" (but only if you are distinguishing from "Eastern Arabic numerals"). In most of the Arabic speaking world (i.e., all but the western-most reaches), the preferred numerical characters are properly called by us "Arabic numerals" or "Eastern Arabic numerals." Now, having dispensed with that ...

I've got a chicken-and-egg uncertainty as to whether the early Arabic world raised mathematical geniuses because of the complexity of their numbers, or whether their numbers are complex because of their mathematical genius. But anyway, they're a smart people with unending oddities in their relationship with the ten digits.

To start: numbers in Arabic are written left-to-right even as the rest of the script is written right-to-left. The following sentence reads, "I have 19 books" and starts at the right:

| ç |

è |

ç |

| كتاب |

١٩ |

عندي |

| books |

19 |

I have |

Also they are challenging because of their often-false similarity to European numbers. And note that the issue of the handwritten style is present with the numbers as well: The handwritten 3 looks like the printed 2:

Arabic

Numerals |

Handwritten |

|

|

| Printed |

|

٠ |

٩ |

٨ |

٧ |

٦ |

٥ |

٤ |

٣ |

٢ |

١ |

| European Numerals |

|

0 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

The upshot is that I (like most beginners) make a lot of mistakes, misinterpreting "false cognates" (as it were) such as the following:

| ١٩٥٥ |

is not |

1900 |

but rather |

1955 |

| ٤٠٦ |

" |

3.7 |

" |

406 |

|

But the oddest aspect of the numbers is the the grammar related to them. I struggle to bring order to this, especially since I haven't learned (in class, with the appropriate exercises and practice) all of this information. But here goes:

Position

- 1-2, the number is usually omitted, but goes after the noun if added for emphasis.

- 3 and above , the number goes before the noun.

Plural

- 1, the noun modified is singular.

- 2, the noun modified is dual (a separate type of plural only for two of an item).

- 3-10, the noun modified is plural.

- 11 and above, the noun modified is singular.

Gender

- 1-2, the number shows gender agreement.

- 3-10, the number shows gender polarity (i.e., uses the opposite gender).

- 11-19, the number shows gender agreement.

- 20 and above, ending in 0, the number does not take a gender.

- 20-99, ending in 1-2, the number shows gender agreement.

- 20-99, ending in 3-9 , the number shows gender polarity.

Declension

- 1-2, the number is an adjective, and thus unaffected by declension

- 3-10, the numbers are diptotes (two cases in a language that normally has more than two cases), with one case dropped in oral usage.

- 11-99, the noun is declined in the accusative.

- whole 100s 1,000s, etc., the number is the first term of a genitive construction.

As an example, you can see increments of كتاب, a masculine noun, and specifically, where it is modified by feminine adjectives, where it is plural or singular, and where the dual plural is added. |

|

| 1 |

|

كتاب واحد |

|

١ |

| 2 |

|

كتابين |

|

٢ |

| 3 |

|

ثلاتة كتب |

|

٣ |

| 4 |

|

عربعة كتب |

|

٤ |

| 5 |

|

خمسة كتب |

|

٥ |

| 6 |

|

ستة كتب |

|

٦ |

| 7 |

|

سبعة كتب |

|

٧ |

| 8 |

|

ثمانية كتب |

|

٨ |

| 9 |

|

تسعة كتب |

|

٩ |

| 10 |

|

عشرة كتب |

|

١٠ |

| 11 |

|

احد عشر كتاب |

|

١١ |

|

| |

|

|

|

An then there's reading a clock. In most languages this is pretty straightforward. In fact, in all of the other languages I've studied (Spanish, French, German, Esperanto, Italian, and Greek) it's almost exactly like English. I'll use Greek as my comparative example:

| Time |

|

In Greek |

|

English Meaning |

| 1:00 |

|

είναι μία η ώρα

|

|

one o'clock |

| 1:05 |

|

είναι μία και πέντε |

|

one and five |

| 1:10 |

|

είναι μία και δέκα |

|

one and ten |

| 1:15 |

|

είναι μία και τέταρτο |

|

one and a quarter |

| 1:20 |

|

είναι μία και είκοσι |

|

one and twenty |

| 1:25 |

|

είναι μία και είκοσι πέντε |

|

one and twenty-five |

| 1:30 |

|

είναι μία και μισή |

|

one and a half |

| 1:35 |

|

είναι δία παρά είκοσι πέντε |

|

two minus twenty-five |

| 1:40 |

|

είναι δία παρά είκοσι |

|

two minus twenty |

| 1:45 |

|

είναι δία παρά τέταρτο |

|

two minus a quarter |

| 1:50 |

|

είναι δία παρά δέκα |

|

two minus ten |

| 1:55 |

|

είναι δία παρά πέντε |

|

two minus five |

But in Arabic it's a much more unfamiliar structure:

| Time |

|

In Arabic |

|

English Meaning |

| 1:00 |

|

ساعة الواحدة |

|

one o'clock |

| 1:05 |

|

ساعة الواحدة وخمسة |

|

one and five |

| 1:10 |

|

ساعة الواحدة وعسرة |

|

one and ten |

| 1:15 |

|

ساعة الواحدة وربع |

|

one and a quarter |

| 1:20 |

|

ساعة الواحدة وثلث |

|

one and a third |

| 1:25 |

|

ساعة الواحدة ونصف إلى خمسة |

|

one and a half minus five |

| 1:30 |

|

ساعة الواحدة ونصف |

|

one and a half |

| 1:35 |

|

ساعة الواحدة ويصف وخمسة |

|

one and a half and five |

| 1:40 |

|

ساعة الثانية إلى ثلث |

|

two minus a third |

| 1:45 |

|

ساعة الثانية إلى ربع |

|

two minus a quarter |

| 1:50 |

|

ساعة الثانية إلى عشرة |

|

two minus ten |

| 1:55 |

|

ساعة الثانية إلى خمسة |

|

two minus five |

|

|

| ح |

|

| |

|

| |

Here's something to wrap your mind around: Traditionally, Arabic does not use punctuation at all – seriously, none. But with the influence of European culture, punctuation marks have been introduced and are now commonly (but not universally) used in Arabic text. Even so, punctuation marks are less common than in English, as Arabic has a complex series of connector words that reduce the need for English-type punctuation.

Where used, however, the marks often reflect a bizarro relationship to their Latin-alphabet counterparts: sometimes backward, and sometimes upside-down. The backward makes a kind of sense in a right-to-left script (although Hebrew is also right-to-left and doesn't reverse its question mark); the upside down, I don't get at all. The quotes are not unexpected: English is the odd language in using what the British call "inverted commas" (a term itself fraught with inconsistency) to frame a quote. Anyway, to cut to the chase, here's what the punctuation marks look like:

| English |

|

. |

|

, |

|

? |

|

! |

|

: |

|

; |

|

“ ” |

| Arabic |

|

. |

|

، |

|

؟ |

|

! |

|

: |

|

؛ |

|

« » |

The Qur'an, you may therefore assume, was recorded entirely without punctuation. This is true insofar as English-style punctuation goes, but as an aid to recitation of the Qur'an, it contains abbreviations to serve as guidance regarding pauses. Examples include:

Punctuation

Abbreviation |

|

Explanation |

| |

Arabic |

|

English |

| م |

|

وقف لازم |

|

compulsory/necessary pause |

| قلى |

|

الوقف أولى |

|

pausing is preferable |

| صلى |

|

الوصل أولى |

|

continuing/joining is preferable |

| لا |

|

لا تقِفْ |

|

don’t pause |

| ط |

|

الوقف المطلق |

|

unqualified pause |

| ج |

|

الوقف الجائز |

|

permissible pause |

|

| |

|

| ط |

|

| |

|

| |

As with other Semitic languages, the structure of Arabic is built around a root set of three (or rarely two or four) consonants. In English, we think in terms of prefixes or suffixes. But in Arabic, because the length of the root is fixed, the transformation of the root into related words is tremendously more complex, with modifications before, after, and within the root. An example of a root is ك ت ب; which references writing; to the right you can see some of the permutations of this root.

The fascinating, sublime part is that you can take a different trilateral root and apply the same permutations to it, and thus achieve (to some extent) parallel related meanings.

(Here, be forewarned, I stray a bit from Arabic, but I hope you'll find the digression worthwhile.) In the year before the trip, one of my few major projects that was not actually related to the trip was reading the superb novel Cryptonomicon and its even more superb prequel, The Baroque Cycle (by Neal Stephenson; read them!). The latter delves into the work of natural philosophers (proto-scientists) at the time of the British Civil War, and one of the side stories introduced me to the (very real) work of John Wilkins on the "Real Character," in which words were augmented based on their logical connections. For example, "de" referred to an element (in Wilkin's time, fire, air, water, and earth); "deb" referred to fire, the first element; "debα" (with an alpha at the end, not an a) referred to the flame, which Wilkins counted as the first "species" of the "genus" deb; and "ded," "deg," and "dep" were, respectively, air, water, and earth. To use a different example, "zi" referred to beasts; "zit" referred to "RAPACIOUS beasts of the DOG kind" (emphasis copied) ; "zitα" (with an alpha) referred to dogs and wolves; "zita" (with an a) referred to foxes. it all seems very orderly until you learn that "RAPACIOUS beasts of the DOG kind" also included "zite" (seals) and "zito" (armadillos). In fairness to Wilkins, he divided "RAPACIOUS beasts" into only two camps: "DOG kind" and "CAT kind," and sorted between them based on the shape of the head. So his fuzzy logic (I use this as a scientific term and not as a value judgment) is internally consistent: Stipulating that a seal is not a dog, the shape of its head is still more dog than cat. Even so, work on the Real Character failed to advance because it could not withstand the degree of conjecture, arbitrariness, and scientific revision that would be necessary for such a language. But the Arabic language evolved in just such a way. Had Wilkins been more aware of it, we might be speaking, or at least might be familiar with, a variant of the Real Character today.

But back to Arabic: The great challenge to the student with this structure comes in using a dictionary. Words are sorted according to the root, and then by part of speech. Thus, all of the words to the right would be collected on the same page of a dictionary. It is as if an English dictionary showed on the same page, "bespoken," "misspoke," "speaker," "spoke," "well-spoken"; it works just fine if you know the language – but if you don't know which of the letters form the root, and which ones are the add-ons, you've got several possibilities to cross-check. |

|

| kataba |

كـَتـَبََ |

to write |

| kattaba |

كـَتـَّبَ |

to make someone write |

| takaataba |

تـَكاتـَبَ |

to correspond |

| istaktaba |

إستـَكـْتـَبَ |

to dictate |

| kitaab |

كِتاب |

book |

| kitaaba |

كِتابة |

writing |

| maktab |

مَكـْتـَب |

office |

| maktaba |

مَكـْتـَبة |

library |

| kaatib |

كاتِب |

clerk |

| miktaab |

مِكـْتاب |

typewriter |

| mukaataba |

مُكاتـَبة |

correspondence |

| mukaatib |

مُكاتِب |

correspondent, reporter |

| muktatib |

مُكـْتـَتِب |

subscriber |

| kutubii |

كـُتـُبي |

bookseller |

| kutayyib |

كـُتـَيِّب |

booklet |

| maktuub |

مَكـْتوب |

written |

| iktitaab |

إكـْتِتاب |

registration |

|

|

| |

|

| ي |

The Plurals and Conjugations and Declensions

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

I am unqualified to document this information, but I'll do my best with the limited knowledge I have gained at this point in my studies.

Our first foray into the Seussian world of logic in which Arabic grammar resides is this: Arabic recognizes only three parts of speech – nouns, verbs, and "letters." Nouns are words which do not have a relationship with time; verbs are words which do have a relationship with time; "letters" (which we would call "prepositions") make the sentence complete. Now I will acknowledge that I may eventually learn enough about Arabic such that this will make sense – but it does not make sense to me yet. Take, for example, the word جديد; this word means "new." It does not mean "newness" or "novelty"; it just means "new." In English we call it an adjective, and not a noun. In Arabic, they have a word for adjective, and they apply this word to the word جديد. And there are rules for how جديد must interact with words which are not adjectives. But at its heart, جديد, in addition to being an adjective, is a noun.

So, to start with nouns. The words themselves are just a vocabulary exercise (perhaps even a bit easier than most languages because of the glorious Root and Patterns system that is the fabric of the Arabic quilt). But Arabic plurals are – to use a term I have learned in my studies of communication – a "pain in the ass." I found one website that gives thirty different patterns, with single word forms resulting in one to five different plural transformations (some of these resultant forms being derived from multiple original structures). And this does not mean that any of the five possible plural forms is appropriate for a particular word structure. No: Only one (or, occasionally, two) of those plurals may be used. Following is the chart I found. (I just wanted you to understand the scope of the issue; don't feel like you have to memorize it.)

| Plural |

|

Singular |

| فعل |

|

فعال |

| أفعلة |

|

فعال |

| فعّالين |

|

فعّال |

| فعّالات |

|

فعّال |

| فواعيل |

|

فاعول |

| مفاعيل |

|

مفعول |

| مفاعيل |

|

مفعال |

| افتعالات |

|

افتعال |

| استفاعالات |

|

استفعال |

| فعلجية |

|

فعلجي |

|

| Plural |

|

Singular |

| فعّال |

|

فاعل |

| فواعل |

|

فاعل |

| فعال |

|

فاعل |

| فعلاء |

|

عاعل |

| فعلاء |

|

فعيل |

| أفعلاء |

|

فعيل |

| فعلى |

|

فعيل |

| فعائل |

|

فعيلة |

| فعالى |

|

فعيلة |

| فعل |

|

فعيلة |

|

| Plural |

|

Singular |

| أفعال |

|

فعل |

| فعال |

|

فعل |

| فعول |

|

فعل |

| أفعلاء |

|

فعل |

| فعلان |

|

فعل |

| فعل |

|

فعلة |

| فعلات |

|

فعلة |

| فواعل |

|

فاعلة |

| مفاعل |

|

مفعل |

| مفاعل |

|

مفعلة |

|

But here's a fun plural fact (and one that makes life significantly less hellish): non-human plurals are treated as feminine singular, both in the adjectives they take and the verbs that pertain to them. (But human plurals take adjectives that are just as elaborately derived from their roots as the nouns [and, by "nouns," I mean of course "nouns-which-are-not-adjectives," lest those of you who have been paying attention take me to task].)

But then come the verbs: Anyone who has studied a Romance language would approach this subject with absolute trepidation. Yet, Arabic conjugations are, finally, the subject which lets the student of Arabic breathe, relax, and say, "All right – that, at least, wasn't so bad." In a language in which memorizing the right pattern for the noun plurals may be likened to a rapacious beast, the verbs are like a gentle lap-dog ("zitαb"; but if you didn't read through the "Root and Patterns" section, you won't get that joke). There is only one pattern, and all the verbs are regular! Of all the languages I have studied, only Esperanto has a simpler verb structure.

Moreover, the prefixes and suffixes that govern conjugations also apply themselves to various other aspects of speech as well. A particularly accommodating example is the نـ or نا that signals "we":

| نعرف |

|

we know |

| عرفنا |

|

we knew |

| يعرفنا |

|

he knows us |

| كتابنا |

|

our book |

| معنا |

|

with us |

Now don't get me wrong: There are oddities with the conjugations. But they are manageable. Notably, verbs are fully conjugated if they come after the noun referenced. But the verb can come first without altering the meaning (it's not like many Romance and Germanic languages, where this turns the sentence into a question) – but in this situation, the verb is in the singular, corresponding essentially to the following: "he says," "says he," "they say," "says they."

Finally, Arabic refers to its linking words as "letters." Some of these exist as short independent words, but I'm sure the term arose because a lot of them are single letters that are prefixed to the next word in the sentence. It sounds like a mess, but you get used to it pretty fast. |

| |

|

| ك |

|

| |

|

| |

The writing is a form of art, but not at the sacrifice of being a vehicle for communication, as this graphic shows. The text is the signature of Mahmud II and reads:

محمود حن بن عبد الحميد مظفر دائما

Mahmud Han bin Abdulhamid muzaffer daima

(Mahmud Han son of Abdulhamid is forever victorious)

Source: Wikipedia; permission granted on source page for re-use.

You can watch the graphic fill in on its own, or you can hover your mouse over the colored words to see the coordinately colored sections of the graphic. Hover over "Black and White" to the right to see the unembellished version as Mahmud II would have written it.

As the graphic fills in, you may notice sections that never turn from the background gray color. This is because they are not characters in the signature, but, rather, are artistic embellishments to complement the rest of the design. |

|

|

| Black and White |

Full Color |

|

|

| |

|

| ل |

|

| |

|

| |

Arabic existed prior to the recording of the Qur'an, of course. But the language is so interwoven with this text that disassociation of the two is inconceivable. The Qur'an, in Islamic belief, was revealed directly to Mohammed by God. Mohammed was said to be illiterate, but miraculously remembered the revelations verbatim and related them to associates who recorded them as the Qur'an.

At the time of this initial transcription, vowel marks and dots had not been introduced to Arabic writing. But in a profound transition, the Qur'an now is always a fully vocalized text, meaning that it includes all of the vowel and diacritical marks, including those that are the most obscure and little-utilized. Today, people get by in Arabic for most purposes without the vowel marks (except, primarily, in political speeches and children's textbooks); but the dots are mandatory and no one would ever think to omit them (except for the maddening and indefensible tendency of the Egyptians to drop the dots in ي and ة). Yet it was not always so: In early Arabic all of the like-shaded characters below would be indistinguishable (at least in some of their forms), and could be known only in context. Below the Arabic characters are the approximate sounds of the characters, to give a better idea of how unlike (in pronunciation) the similarly shaped characters are. (N.B.: This has led to disputes among Qur'anic scholars as to the meaning of certain passages.)

| ـيـ |

ـو |

ـهـ |

ـنـ |

ـمـ |

ـلـ |

ـكـ |

ـقـ |

ـفـ |

ـغـ |

ـعـ |

ـظـ |

ـطـ |

ـضـ |

ـصـ |

ـشـ |

ـسـ |

ـز |

ـر |

ـذ |

ـد |

ـخـ |

ـحـ |

ـجـ |

ـثـ |

ـتـ |

ـبـ |

ـا |

| Y |

W |

H |

N |

M |

L |

K |

K |

F |

? |

? |

TH |

T |

D |

S |

SH |

S |

Z |

R |

TH |

D |

KH |

H |

J |

TH |

T |

B |

A |

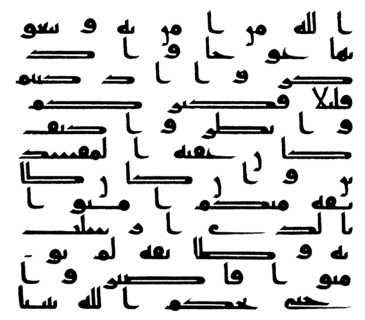

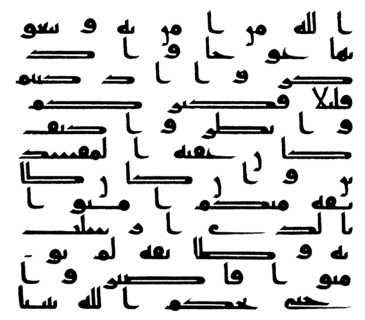

In fact, it was specifically to preserve their holy text without ambiguity that led the early Islamic community to develop the vowels and then the dots. An example of the alternative can be seen in the following Kufic undotted text.

See, that's a lot harder to read, isn't it?

Another interesting (and more modern) bit of Arabic history regards the dialects. The written language is standard and is used throughout the Arabic-speaking world. But the street language differs so much from (for example) Morocco to (for example) Syria that the people cannot immediately understand each other across these extremes. But it was not a major city, not a university, not an institution that was regarded as the enclave of pure Arabic; rather, it was the rural Bedouins who were thought to speak the language without adulteration. Even in the not-too-distant past, wealthy families might send their sons to live in the desert so they could learn to shoot accurately, hunt effectively, and speak properly. |

|

| Driving Down to the Dead Sea |

We drove south on Jordan's Dead Sea highway, wanting the experience of swimming in the EN Dead Sea HE ים המלח AR البحر الميت . What we got instead was an experience that included swimming in the Dead Sea. Here's how it went down: Pretty early in the trip, we came to the resort areas. I went past because (1) I'm cheap and I knew the hotels would charge for use of their beachfronts and (2) it wasn't clear at the time they were open (because a major new hotel was under construction, but I know now that the Mövenpick and the Marriott were operating). So we kept driving and eventually came to a pull-off where the locals seem to go for the Dead Sea experience. This was basically a litter-strewn camp of folding tables on one side of a high-speed roadway, and a row of parked cars on the other side.

We walked up to one of the tables where they seemed to be selling some things and pursued a conversation in broken Arabic and broken English. We started by asking if there were a restaurant in the vicinity. And the guy behind the table said yes, this is a restaurant. This confused us, because to our eyes it clearly wasn't – so we asked what he had. And he asked what we wanted. And we asked what he had again. And because he pointed to some containers that looked like food products and because he was clearly trying to be helpful, I finally decided it was worth plunking down a couple of dinars to avoid looking like a rude imbecile. So he showed us to an adjacent folding table (it really was a restaurant, after all!) and put down some plastic plates, and opened a can of pressed lunch meat (but not Spam, for obvious reasons) which he dumped it on the center plate and sliced with a pocketknife, and opened a container of yogurt, and gave us some bread for the yogurt (in the absence of utensils), and set a liter-and-a-half of water down for us to share (without glasses to pour it in). And we ate thusly on the banks of the Dead Sea.