يوم الثلاثاء، ١٣ ربيع الثاني ١٤٢٨

| 20 | ٢ | |||

| 21 | ٣ | |||

| 22 | ٤ | |||

| 23 | ٥ | |||

| 24 | ٦ | |||

| 25 | ٧ | |||

| 26 | ٨ | |||

| 27 | ٩ | |||

| 28 | ١٠ | |||

| 29 | ١١ | |||

| 30 | ١٢ | |||

| 1 | ● | ١٣ | ||

| 2 | ١٤ | |||

| 3 | ١٥ | |||

| 4 | ١٦ | |||

| 5 | ١٧ | |||

| 6 | ١٨ | |||

| Getting our Bearings |

Dearly needing our rest, we slept late – but not late enough to miss the delicious breakfast at the Amon, which we ate in the tranquil garden around which the hotel, and its reputation, are built.

|

|

Now perhaps you're thinking, "Jeez, why does he keep showing us toilets." Well, it's because I learned a lot of stuff about toilets on this trip and now I have to document it so I don't forget. And really, toilets come up a lot in traveling. In movies, the iconic clue that the scene has shifted to Europe comes with a donkey-braying ambulance in the background – but in reality, one's own experience of "yikes, this ain't like home" comes upon walking into the restroom: Who among us hasn't stood at some point in our lives in a tiny room on the continent and wondered, "What, precisely, am I expected to do on a bidet?" or "How the hell do you flush this thing?" Perhaps if there were more toilet détente in the world, various nations could agree on best practices, and a universal supertoilet could arise. But until that day, traveling brings just as many amazing discoveries at this stage of the digestive process as it does in that jaunty little café with the fabulous view where it all started.

Toilets were really an issue for us from beginning to end: Remember that we've been forbidden to flush toilet paper since we landed in Greece about ten weeks ago (or so it felt), and then we encountered the dual flush thingy in Israel and Jordan, and a "floor-hole" toilet in the hygiene hut at the desert camp. And now this we have the bidet attachment built in. We never encountered anything as horrifying as the jungle toilet in Belize (wooden plank, square hole, open air), but still, toilets were on our minds. With every new hotel room, we went to the bathroom first just to answer the question, "What is it going to be like this time?"

And, as you see in the picture, this time it had the bidet attachment. So I turned to faithful Wikipedia upon my return to understand why Egypt had these things on every toilet we encountered. (Maybe Jordan did too in most places – but the Taybet Zaman was very Western, and the desert camp was very rustic.) The answer, it turns out, is

Istinjaa

Paraphrased from resources at the University of Southern California. But the story doesn't end there: The instinjaa procedure is often cited by adherents as evidence of the beauty and fullness of Islam. Say they: If the teachings go into this level of detail, then you know that nothing in the faith is left to chance. Thus, you are guided with precision regarding when the bidet attachment is warranted:

And if that leaves you wanting for clarity, then there's this:

|

Now for obvious reasons, this flow chart is impractical even if you know how much a dirham weighs. I cannot enlighten you any more than I already have about the istinjaa decision tree – but I can, at least, close the gap regarding the dirham:

|

Beyond the restroom, though, there were other challenges: I had in my pocket 98 Jordanian dinars, in a country where they were unrecognized and unacceptable, and there are no ATM machines or banks on the West Bank in Luxor. The only way to get to an ATM was to cross the river, which required using a ferry, which necessitated having Egyptian money, which was across the river. The proprietor of the Amon very generously lent me LE 110, which was my life raft to solvency. (By the official exchange rate, this equates to $19.36, but such a conversion cheapens the generosity; in the context of Egypt's economy, it was not unlike lending me $110.) He also told me that the ferry was LE 1 (18¢) and private boats were LE 5 (88¢), so I wouldn't overpay.

So we left the Amon, finally seeing the streets around it in daylight, and learning how to use the ferry.

|

|

And it's a good thing we were warned about the ferry fare, as they tried to rip me off: I handed the fare collector a LE 10 bill for me and Billy and he only gave me back LE 6. I shamed him for the effort and he sheepishly gave me the extra LE 2. Actual dishonesty of this sort, however, is uncommon – and I realized early in the trip that I had come to Egypt so wary of scams that I was finding it difficult to trust even when trust was appropriate. Fortunately, that realization came early and I had time to reassess, and many counterexamples to steer me – not only the trusting generosity of the hotel proprietor, but other things as well – including a kid in a restaurant who literally chased a man over a block down the street to return sunglasses he had left behind in the kid's restaurant.

The ferry is not heavily used by tourists and is a bit of a chaotic experience: People jump on even as the boat is moving from shore; there are no life preservers; the exit steps are not roped off; and as soon as the boat comes within about a meter of shore, people start clambering out through the proper exits and over the rails.

So we got across the river and I finally got to an ATM. Now remember that using foreign currency is always a joy for me – and I was already excited about the Egyptian bills, as they have an interesting structure: One side is written in Arabic and displays pictures of famous mosques in the country while the other side is written in English and generally displays pictures relating to Egypt's ancient history and tourist trade (for which there is almost complete overlap). Now some might characterize this as an identity crisis, but I liked it. There are other aspects of the money, however, that extend the identity-crisis theme, notably the way it is designated: I have used "LE" here, as that is most common; it stands for the phrase

I've already let a tone of judgment seep in, though, haven't I? Okay, let's lay the cards on the table: This currency is crap. Never in my life have I used anything so repugnant for payment. Sometimes I found myself buying things just to get rid of the filthy, flimsy money. The root of this problem is that it is printed on ordinary paper, not the elegant "cloth" papers that are used for the U.S. dollar, the euro, and the Israeli new sheqel – so it turns into a wispy, soggy, playground for bacteria in almost no time at all. But a major contributing problem is the lack of coins; the Egyptian government does mint coins (even duplicating a lot of the paper money denominations), but you almost never encounter coins. Even for 25 Pt. (4¢) you'll receive a ratty, purple sheet of paper that used to look like a banknote. Imagine if we never used pennies and had bills for everything down to the nickel. And in the other direction, the most valuable bill in production is LE 100 ($17.60), so there's no such thing as a bill of high enough worth that it is likely to be clean and crisp and new.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

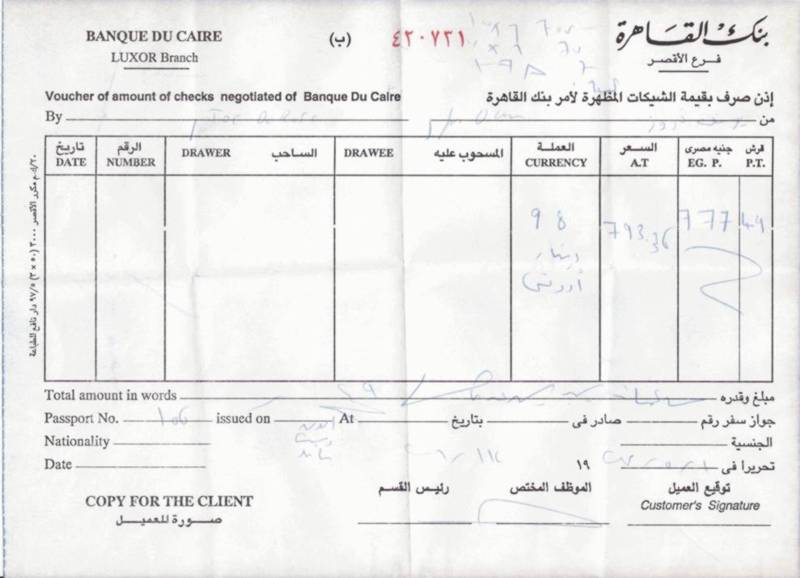

After getting cash, our goal was visiting Karnak. To this end we hired a calèche to take us there for LE 30, and I climbed two learning curves – one relating to this bartering system and the other relating to currency exchange. I had mentioned to the calèche driver that I would like to try to convert my Jordanian dinars at some point, and he offered to stop by a bank on the way. Because dollars and euro are accepted so readily, and because the kids the previous night accepted my dinari as a tip so enthusiastically, I had assumed that currency exchange would be a snap – but through a series of problems and convolutions, I had to stop in one bank after another before I could make the conversion. (At one, the person with the authority to accept foreign currency was at lunch; at another they sent me away because the power had gone out and the mainframe computers were taking too long to reboot; at a third, the only person authorized to compare dinars with the pictures in the book had taken the day off.) Finally I came to a bank where they intended to send me away again, but a respected person was in the lobby at the same time and vouched that my dinars were legitimate, and they made the conversion:

|

Receipt for My Conversion of Dinars to Pounds |

The other component of the learning curve arose when we got to Karnak. I knew that I should pay more than the agreed-upon rate of LE 30 ($5.28), because the detours had gotten a bit lengthy. I thought I was being generous in offering LE 50 ($8.80), but the calèche owner started moaning that this wouldn't even feed the horse, that the one-hour ride had become two (it had actually become one and a half, and that was only because he insisted on taking us by a papyrus vendor who would have given him a kickback on any purchase we made), and that I should be ashamed to offer so little. He insisted on LE 80 ($14.08). I stood my ground at LE 50. He acted infuriated by my selfishness (but was all smiles when he saw me the next day, imploring me to use his services again).

So I learned that I should always do exactly the agreed-upon thing for the agreed-upon amount, and neither request nor allow any deviation from the plan. I also learned that I hate haggling for several reasons: It is a waste of time. It is stressful. And it makes me feel like a jerk: I don't want to be the "easy mark," but I found myself quibbling over trivial amounts for things that would be a lot more expensive in America (and that I would frankly be willing to pay a lot more for, if only I could be sure that everyone else was paying more as well).

| The Temple at Karnak |

The temple at

You'll notice that the layout of Karnak does not bear evidence of a strategic plan. This is because the ancient Egyptians considered their temples living entities that would grow and enlarge organically. The temple complex at Karnak is divided into three precincts:

|

The Temple at Karnak |

But only the main one, the Precinct of Amun-Re, was open to the public.

|

The Precinct of Amun-Ra |

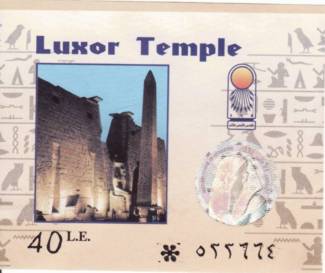

So we bought our tickets, fought our way past the vendors, and approached the First Pylon past the Avenue of Sphinxes.

|

|

And past the First Pylon, we came to the Great Court ("Great Forecourt" on the map).

|

|

And then we got to that most spectacular area, the Hypostyle Hall ("Great Hypostyle Hall" on the map), which is without a doubt the pièce de résistance in this architectural masterwork.

|

|

Past the Hypostyle Hall, we got to see a couple of obelisks, which were amazing in that they were (1) still standing (2) in Egypt – the obelisks of

EGY Khnumt-Amun Hatshepsut

EGY Khnumt-Amun Hatshepsut

|

|

And then we got to an area with some spectacular hieroglyphics, some still carrying visible pigments of what I hope and assume was their original form. To my naïve understanding, the structure of the temple gets a bit jumbled at this point, but this area included both the Sanctuary of  EGY Thutmose Neferkheperu

EGY Thutmose Neferkheperu

|

First we came to the area with the cool hieroglyphs, which I suspect was the Sanctuary of Phillip Arrhidaeus: |

| The Temple at Luxor |

From Karnak Temple, we took a taxi to the smaller Luxor Temple, which I found, like many, to be an elegantly scaled-down counterpoint to the grandeur of Karnak.

|

Luxor Temple |

"Scaled-down," though, is a relative concept. The entry to Luxor, with the Pylon of  EGY Ramesses Meryamun

EGY Ramesses Meryamun

|

|

First we went to the Court of Ramesses II, just beyond the Pylon of Ramesses II (he was probably not the most self-effacing of pharaohs), and sat there to soak in the preternatural heat and the beauty of this temple.

|

|

Farther in, we came to the Colonnade of  EGY Amenhotep Hekawaset

EGY Amenhotep Hekawaset

|

|

Finally, we exited Luxor Temple, taking a few minutes to walk up and back on (what's left of) its Avenue of the Sphinxes.

Avenue of the Sphinxes |

Perhaps by now you have come to join me in wondering, "What, precisely, is a 'sphinx'?"

|

An interesting etymological note is that because of the traffic jam created by the Sphinx in definition 2, "sphincter" comes from the same root.

There are by the way, three varieties of sphinxes:

- Androsphinx - body of lion with head of person (such as those in Luxor, and the big one in Giza);

- Criosphinx - body of lion with head of ram (such as those in Karnak); and

- Hierocosphinx - body of lion with head of falcon or hawk.

Now you might expect me to wait for the sphinx thing until we got to Giza where the Sphinx in definition 1b rests, but this is really the most auspicious time for the discussion, as here in Luxor we were in "sphinx central": First, even in modern times we facing an embarrassment of riches in the sphinx department with the dual avenues of the sphinxes here and at Karnak, but in ancient times this Luxor "Avenue of the Sphinxes" used to be exactly that – running the whole 2.5 km (1.6 miles) to Karnak. (But the avenues of the sphinxes were not opposite ends of the same road; the one at Karnak runs northwest from the temple, and Luxor is to the southwest.) And not only that: Though I have been calling this city by its modern name of  EGY Waset

EGY Waset

And it is under the illustrious name "Thebes," rather than "Luxor," that this place is recognized as a World Heritage Site.

| World Heritage Site | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

By this point, however, the heat was taking its toll on us, and we hobbled to the ferry, across the Nile, and up to the respite of our hotel.

Dinner was a feast of pita bread, tomato soup, salad, tomatoes and peppers, rice, potatoes in tomato sauce, and watermelon, all to accompany the entrée – Billy had chicken and I had

| Main | ||||||||

| 20 | κʹ | |||||||

| 21 | καʹ | |||||||

| 22 | κβʹ | |||||||

| 23 | κγʹ | |||||||

| 24 | κδʹ | |||||||

| 25 | κεʹ | |||||||

| 26 | ח׳ | |||||||

| 27 | ט׳ | |||||||

| 28 | ١٠ | |||||||

| 29 | ١١ | |||||||

| 30 | Previous | الأخير | ١٢ | |||||

| 1 | ١٣ | |||||||

| 2 | Next | التالي | ١٤ | |||||

| 3 | ١٥ | |||||||

| 4 | ١٦ | |||||||

| 5 | ١٧ | |||||||

| 6 | ١٨ | |||||||