Τρίτη, κδʹΑπριλίου ͵βζʹ

| 20 | κʹ | |||

| 21 | καʹ | |||

| 22 | κβʹ | |||

| 23 | κγʹ | |||

| 24 | ● | κδʹ | ||

| 25 | κεʹ | |||

| 26 | κϝʹ | |||

| 27 | κζʹ | |||

| 28 | κηʹ | |||

| 29 | κθʹ | |||

| 30 | λʹ | |||

| 1 | αʹ | |||

| 2 | βʹ | |||

| 3 | γʹ | |||

| 4 | δʹ | |||

| 5 | εʹ | |||

| 6 | ϝʹ | |||

| The Smart Car |

We picked up the Smart car early this morning for our explorations of Crete, and found nothing whatsoever to support warnings about Greek drivers ("erratic and aggressive"): Indeed, their style was notable only for a slightly greater courtesy than in other parts of Europe that I've visited – significantly, I saw them stop occasionally for pedestrians waiting at the curb, which I've never seen anywhere else in Europe; usually a certain boldness on the pedestrian's part is required. (Again, traveling teaches you that everything everyone says is wrong.)

I had really been looking forward to the Smart car. Not only was it an unusual type of vehicle, but it had an unusual shifting mechanism: a semi-automatic transmission (gear shifting, but no clutch). Unfortunately, I didn't bond with it, precisely because of the transmission: The linear up/down system made it hard to skip gears, and the lag threw off my timing, making passing difficult. I could have done much better with a clutch. Apparently, they are quite popular, though: Even though the car is cheap, it is rented in the luxury category (€ 65.00 [$88.84] per day). I could have gotten a bigger car for a lot less, but I wanted this experience.

|

|

| Knossos and Phaestos |

|

Knossos |

We headed out from Iraklio immediately, to see

Knossos is particularly famous not only as the most accessible of the Minoan cities, and the likely capital of their civilization, but also as the site associated with the legend of the Minotaur, a half-man-half-bull that lived in maze under the palace (or, in some variations, in the maze-like palace itself). For those who want to know the legend, here it is:

The Minotaur According to the historian Thucydides, writing in the fifth century BC, it was the Cretan king Minos who built the first navy and dominated the known world (to the ancient Greeks, this meant the Aegean). Minos was the son of the god Zeus and Europa, the mortal daughter of the king of Phoenicia. Zeus was dazzled by her beauty and, for reasons best known only to himself, decided to appear before her in the guise of a snow-white bull. Unlikely as it may seem, the plan worked. Europa was tantalized by his enormous dewlaps and his gentle demeanour and began to play with him, decorating his horns with garlands of flowers. She even took to climbing on his back and riding him, but one day he suddenly plunged into the sea and swam away with her. He swam all of the way to Crete and, upon coming ashore, changed himself into an eagle and raped her. The myth is generally believed to have developed around the seizure of the island by Mycenaean Greeks from the mainland in the 15th century BC and the triumph of the patriarchal sky god over the local mother goddess. Europa gave birth to three sons by Zeus – Minos, Rhadamanthys and Sarpedon – and, when he abandoned her, she married Asterion, the king of the island. Their marriage was childless, however, and he adopted the boys as his own. After his death, he was succeeded by Minos who, with the help of Poseidon, gained control of the island. However, the king tried to cheat the god of his reward, the sacrifice of a snowy white bull, and substituted a lesser animal from his own herd. As a punishment, Poseidon caused Minos’ wife, Pasiphaë, to fall passionately in love with the bull and she begged Daedalus, the legendary craftsman, to help her satisfy her lust. So Daedalus built a wooden cow, hollow and upholstered with leather inside so that the queen might lie within. The result of their unnatural union was the Minotaur, half man and half bull, whom Minos ordered hidden, along with his mother, at the centre of a maze underneath his palace at Knossos. The palace was known as the Labyrinth, a term that was apparently related to the pre-Greek word labrys and probably meant “House of the Double Axe.” Minos and Pasiphaë had several other children, including Androgeos, Ariadne, and Phaedra. When Androgeos was killed by the Athenians, Minos went to war to avenge his death. He defeated the Athenians and extracted a tribute of seven youths and seven maidens who were sent to Knossos every nine years to be fed to the Minotaur. On the third occasion of the sacrifice, Theseus, the son of the Athenian king, offered to go in the place of one of the victims. When he arrived in Crete, the princess Ariadne instantly fell in love with him and offered to help him slay the monster. She gave him a sword and a ball of thread, which he unrolled as he made his way to the heart of the Labyrinth and killed the beast. He then retraced his steps, freed his comrades and they all sailed back to Athens, including Ariadne whom Theseus had promised to marry. However, when they reached the island of Naxos he left her sleeping under a tree and returned home without her. According to some versions of the story, she hanged herself in despair but in at least one account she was rescued by the god Dionysus who married her. Source: Odyssey Adventures |

As for myself, my eyes start to glaze over about when Pasiphaë is having sex with the hollow wooden cow; I had to read this thing about seven times before I finally made it to the end. And I really fear that I'm not the same person as I was before my eyes passed over the phrase, "tantalized by his enormous dewlaps." And what's up with that whole ball-of-thread thing? If the maze was so complex that Theseus couldn't find his way out, it shouldn't be too hard to dodge the Minotaur; and if the Minotaur was dead, he's not under any time pressure to make his escape. (Now I remember why I hated mythology in school.) I'm inclined to dismiss it as the drug-addled ravings of an ancient civilization – but apparently, if you know what you're looking for, you can find in this sort of narrative oblique references to the history, culture, and politics of the Minoan civilization.

Being able to see both Knossos and Phaistos in the same day was a rare educational opportunity, as the sites, when discovered, were extremely similar to each other – but the former was restored substantially (and with no small number of creative assumptions) by Arthur Evans, who purchased the excavation at the turn of the 20th century: Walls were rebuilt; rooms were arranged; frescoes were repainted based on fragments. By contrast, Phaestos was left more or less as it was found. The upshot was that Knossos taught us more about the limits and licenses of archaeological restoration than it did about the Minoans.

In fairness, though, to Evans, archaeology is an evolving discipline. Just as in economics or political science or sociology or psychology, much of what we know today in archaeology is known only because of what we learned from previous mistakes. And much of what we do today with the best of intentions will similarly enlighten future generations – not as noble work, but as unfortunate blunders. And even our generation of archaeologists wrestles with the question of whether to preserve in situ the layers that they can see, or whether (and how) to investigate what may be underneath. When Evans began excavating Knossos in the spring of 1900, archaeology was underfunded by governments and universities, and in that void these endeavors were pursued by wealthy adventurers. In this context, Evans was among the best of the lot. He may have rebuilt parts of Knossos, but he didn't plunder it. And, in honesty, some of his rebuilding was conducted less out of fanciful indulgence, and more out of an effort to protect his finds from the elements.

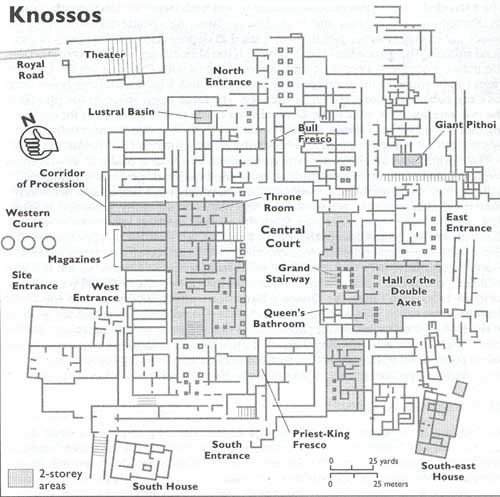

It was Evans who coined the name of this civilization – "Minoan" – after the legendary King Minos. Some accounts place King Minos as living in Knossos – but this only cracks the lid to a Pandora's box of uncertainty: It is not known with certainty whether Minos was even a living being, or a purely mythological figure. It is not known whether there was only one, or two, kings "Minos" (as two would explain the vastly different temperaments ascribed to this name). And it is not even known if the word "Minos" was even a name at all, or just a word meaning "king." Evans has been accused of superimposing the familiar British monarchy over Knossos, and it was he who described this place as a "palace," and who fleshed out the areas used by the kings and queens of the palace. Later investigations have suggested that in modern parlance, it may be more accurate to think of Knossos as a temple or an administrative center or a theocratic combination of the two; another, less popular viewpoint, is that it may have been a necropolis.

Remember that in Mexico Billy and I had the good fortune to stay in a hotel run by a retired archaeologist. Valente Quintana's opinions on rebuilding were highly refined and strongly felt, and came to influence our own: His view was that, if you saw a rock on the ground and a void of the same shape on a wall above, it was okay to put the rock in the void. But you would never move a fragment if there was any ambiguity about where it had originally been placed. And you would never, never, never carve new forms to recreate the whole. He thought Chichén Itzá was "Disneyland"; he would have been horrified by Knossos.

But we knew what to expect, and we were there to see it – "Disneyland" or not. First we had a phenomenal breakfast across the street, and then we plunged into the Knossos; the following set of pictures shows the most profound examples of rebuilding. It is generally conceded by archaeologists that these structures are unlikely to match the appearance of the site during any point during its prior history.

|

|

Still, there are some nice areas that don't appear to be reproductions:

|

|

One of the most spectacular (and substantially reconstructed) areas of Knossos is the throne room.

|

|

But the real joy of Knossos was really just its gorgeous setting, in the lush Cretan countryside.

|

|

And for all of my grousing about dodgy restorations, it is worth noting that serious archaeological work continues at Knossos.

Archaeologist at Work in Knossos |

We did some shopping across the street (for a tourist strip, the stores were actually of very high quality). Then we were on to

|

|

The Minoans were geniuses at water management, and had three different systems: one for water supply, one for sewage, and one for runoff. Now to put that in perspective: The city of Atlanta is struggling under court order to correct for pollution caused by the fact that our system was built, at least 3,350 years after Knossos and Phaistos, without a separation between sewage and runoff.

|

|

| Gortyna |

Now keep in mind that Billy and I are not archaeological experts. We're really not even particularly well-informed. The shameful truth is that we just like going and looking at old pretty stuff. So with that disclaimer, the truth is that we found Knossos and Phaistos interesting, but a tad underwhelming. We had come here because Billy had seen a special on Knossos, and thought it looked cool, and I had come to trust his instincts after following his excellent recommendation to make

But the day was not a loss (even in our ill-informed opinions) and was even more spectacular than it might have been because we found

- Archaeologically: There are ruins here going back to 7000 BCE, including the Gortyn Code, which is the oldest and most complete example of ancient Greek law.

- Historically: It was capital of Crete under Roman rule and was the first city on the island to accept Christianity.

- Naturally: it has a deciduous plane tree, one of only 50 of this extremely rare subspecies on Crete.

- Mythologically: The aforementioned plane tree is where Zeus had his affair with Europa, from which the entire European civilization was born (and that whole Minotaur thing got going).

So let me tell you, if you go to Crete, don't miss Gortyna!

The introduction to the site is the spectacular ruin of the Cathedral of St. Titus, a three-aisled basilica that was built to replace the nearby, much grander (five-aisled) Great Basilica, which has lain completely in ruins since an earthquake in 670 CE.

|

|

We worked our way to the back of this incredible site:

|

We didn't know about the legend of the plane tree, and though we saw it, we didn't photograph it because the signs were only in Greek. (I assumed at the time it was just a simple tree dedicated as part of a cultural exchange of some sort.) In ignorance, therefore, we were more impressed with this very comely grove of olive trees near the Cathedral of St. Titus: |

But it was behind the Odeon that we found the most spectacular thing that Gortyna has to offer (and in saying this, I agree with most archaeologists and historians): The Gortyn Code. As someone fascinated with language and writing, I particularly enjoyed the fact the the Gortyn code was was boustrophedonic (meaning that it runs alternately left-to-right, then right-to-left, taken from the Greek word

|

|

And finally, there were some very nice sculptures in the adjacent museum. Unfortunately, there was no information to inform us what we were seeing, what era it represented, where it was found, and whether it was the original or a reproduction.

|

|

| ... And the Rest |

In case my reference is too obscure, I titled this section in homage to what my generation remembers as the iconic reference to unimportant items in a list.

The ship's aground on the shore of this Gilligan's Island |

The ship's aground on the shore of this Gilligan's Island |

The incessant pre-trip criticism was that we had scheduled too much, and should have allowed ourselves longer times to see these amazing places. I will concede that I wish we'd had more time between places (see the FAQ), but we had all the time we needed at places. To wit, we had seen Knossos, Phaistos, and Gortyna, and it wasn't even getting on toward suppertime yet. So we decided that we would drive around in central Crete, stopping at every single place we could find with a historical marker, and see what these minor attractions were all about.

The first of these sites was around the corner from Gortyna, marked as the

|

|

But in truth, I was far more interested in what I found a few feet away, when I turned the car around on this dirt road: A farmer had used ancient columns from the ruin fields nearby to mark the edge of his driveway. It's endlessly fascinating to me to discover what various people in various places take for granted.

Ancient Columns Being Used as a Driveway Marker |

Then we continued down to the Mediterranean (southern) coast, past the very small, very quaint, and very satisfying

|

|

So we drove to the coast and saw the Mediterranean proper for the first time (all of the other times we were looking out at subsets, like the Tyrrhenian Sea, the Ligurian Sea, the Adriatic Sea, or the Aegean Sea – but finally this was unambiguously it: The Mediterranean). We tried to dip our hands in the surf just to say we did, but a surprise wave got us up to the ankles.

Then we had dinner at a pleasant coastal restaurant that would have been perfectly at home on Tybee. I followed the waiter's recommendation for shrimp Mediterranean – heads-on prawns in a delicious sauce, at a rip-off price of € 15 for four.

And then we returned to Iraklio, past the

|

|

At Gortyna, Billy and I both commented that it felt like we had been on vacation forever, and that if we had to return home tomorrow it would feel like a complete and wonderful experience. It was hard to believe we had 12 days left.

As someone who enjoys languages, I was looking forward to being surrounded by Greek writing, but did not have high hopes of being immersed in it as English is so ubiquitous everywhere we go. But Greek is thriving – and especially in southern Crete I found few examples of the Latin characters (except, of course, on roadway signs and untransliterated product names). I'm really glad I learned to sound Greek out, as this helps in looking for cognates. And I came to worry about Hebrew, which I never learned to pronounce, although this never proved a problem when we moved on to Israel.

We returned to Iraklio with time to spare, but fortunately were able to board the ferry early. So we returned the car and walked over to the nearby port to secure our rooms on the Minoan Lines Knossos Palace – which was enormous, with a mall, several restaurants, all sorts of fitness offerings, a floating hotel, and room for 600 cars. Indeed, I would not be surprised to learn that there is more floor area in the ferry than in the ancient palace for which it is named. Our cabin on the ferry was the nicest of our hotel rooms so far.

|

|

| Main | ||||||||

| 20 | κʹ | |||||||

| 21 | καʹ | |||||||

| 22 | κβʹ | |||||||

| 23 | Previous | Προγενέστερος | κγʹ | |||||

| 24 | κδʹ | |||||||

| 25 | Next | Επόμενος | κεʹ | |||||

| 26 | ח׳ | |||||||

| 27 | ט׳ | |||||||

| 28 | ١٠ | |||||||

| 29 | ١١ | |||||||

| 30 | ١٢ | |||||||

| 1 | ١٣ | |||||||

| 2 | ١٤ | |||||||

| 3 | ١٥ | |||||||

| 4 | ١٦ | |||||||

| 5 | ١٧ | |||||||

| 6 | ١٨ | |||||||